Price threshold analysis of biomarker surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in Australia

Abstract

Aim: Novel biomarker panels may have comparable performance to ultrasound with alpha-fetoprotein (US-AFP) in the surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) among individuals with cirrhosis. We performed an economic modeling study to estimate the threshold price at which biomarker-based surveillance would be cost-effective in the Australian healthcare setting.

Methods: We constructed a Markov model to evaluate three strategies: no surveillance, US-AFP surveillance, and biomarker surveillance based on the recently reported GAAD algorithm (gender, age, AFP and des-γ-carboxy prothrombin). The threshold price of biomarker surveillance was estimated relative to US-AFP, using a willingness-to-pay threshold of A$50,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). The base-case analysis assumed an annual HCC incidence of 2% and 70% adherence to surveillance. Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate uncertainty in biomarker performance, HCC incidence, and surveillance adherence.

Results: In the base-case scenario, biomarker surveillance yielded a 0.02 QALY gain compared with US-AFP surveillance and a 0.07 QALY gain compared with no surveillance. Relative to US-AFP, biomarker surveillance was cost-effective if priced at ≤ A$454 and dominant if priced at ≤ A$310. Sensitivity analyses showed that the biomarker threshold price ranged from A$165 (with 50% adherence) to A$838 (with an annual HCC incidence of 5%).

Discussion: Biomarker surveillance is a promising intervention for HCC surveillance in people with cirrhosis. Our results suggest that, in the Australian context, it is likely to be cost-effective - and potentially cost-saving - when compared with the existing standard of US-AFP surveillance.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most prevalent form of primary liver cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide[1]. It typically develops in people with established cirrhosis, most often due to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcohol-related liver disease (ARLD), or metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)[2,3].

All major hepatology guidelines recommend HCC surveillance with ultrasound and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) testing every six months in people with compensated cirrhosis[4-7]. The purpose of surveillance is to detect HCC before the onset of symptoms, thereby increasing the likelihood of curative treatment options such as surgery, ablation, or liver transplantation. Early detection through surveillance has been shown to improve survival outcomes in at-risk patients[8,9]. However, this strategy is limited by suboptimal sensitivity, specificity, and uptake, prompting investigation into alternative strategies[10].

Biomarker-based surveillance has attracted significant interest as a potential alternative[11]. Among candidate markers, des‐γ‐carboxy prothrombin (DCP) and the lens culinaris agglutinin‐reactive fraction of AFP (AFP‐L3) are particularly specific for HCC detection[12-14]. Several composite scoring algorithms incorporating these biomarkers have been developed, including GAAD (gender, age, AFP, DCP) and GALAD (gender, age, AFP-L3, AFP, DCP). A recent validation study has demonstrated that longitudinal application of the GAAD algorithm is highly sensitive for detecting both early- and all-stage HCC in cirrhotic patients[15].

In addition to diagnostic performance, cost-effectiveness is an important consideration in cancer screening. Prior economic evaluations have established ultrasound surveillance as cost-effective for cirrhotic patients[16-18]. A recent U.S. study by Singal et al. suggested that biomarker surveillance using the GALAD panel may also be cost-effective[19]. Based on American Medicare fee schedule costs, the authors reported an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of US$101,295 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) in their base-case analysis, meeting the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of US$150,000 but not US$100,000 for cost-effectiveness. The relative cost-effectiveness of biomarker surveillance compared with ultrasound, however, was heavily dependent on biomarker test sensitivity, test price, and adherence to screening. In probabilistic sensitivity analyses, biomarker surveillance was the most cost-effective strategy in 65% of simulations at a WTP threshold of US$150,000.

Given geographical variation in healthcare costs and delivery, economic modeling within individual health systems is essential. Novel biomarker panels are not presently available in Australia. Therefore, the primary goal of this economic analysis was to determine the threshold price at which a biomarker panel would be cost-effective in the Australian healthcare setting compared with the existing standard of care - ultrasound with AFP (US-AFP). We also sought to establish the biomarker threshold price relative to no surveillance for HCC. Our model was based on Australian healthcare and economic data and incorporated the diagnostic performance of the GAAD algorithm, given its promising results in recent validation studies[15].

METHODS

This economic evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement[20].

Study design and Markov model

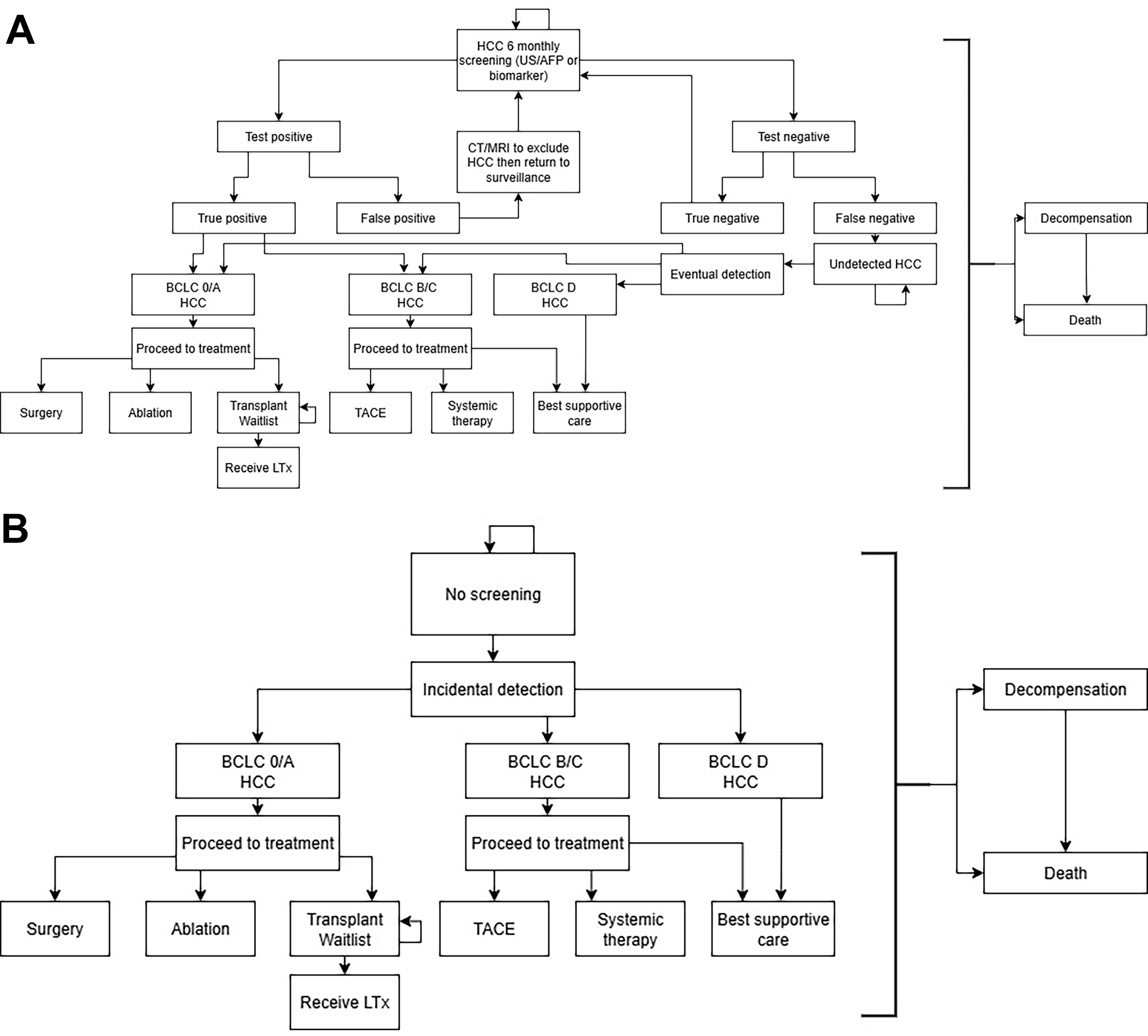

We developed a Markov model using Treeage Pro 2024 to evaluate three HCC surveillance scenarios: no screening, surveillance with US-AFP, and biomarker-based surveillance. The simplified model structure is shown in Figure 1, illustrating the health states and transitions for each strategy. The full model is presented in Supplementary Figures 1-3. Our model captured the natural history of cirrhosis and HCC, from detection through treatment, recurrence, and death. HCC could be detected either through surveillance or incidentally if surveillance was not used (no-surveillance scenario or missed surveillance). We also incorporated the risk of detecting non-HCC liver lesions and the downstream costs of further investigations. Competing risks, including hepatic decompensation and background mortality, were included. The model cycle length was six months, consistent with guideline-recommended surveillance intervals[4-7].

Figure 1. (A) Simplified state-transition model for HCC surveillance (US-AFP or biomarker-based); (B) Simplified state-transition model for the no-surveillance scenario. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; US-AFP: ultrasound with alpha-fetoprotein.

The starting age was set at 40 years, and 60 cycles (30 years) were simulated. In the base-case analysis, the annual incidence of HCC was assumed to be 2%. Adherence to either surveillance strategy was set at 70%. Both costs and QALYs were discounted at the Australian standard rate of 5% per year.

Model parameters

We reviewed the literature to determine costs, utilities, and transition probabilities, prioritizing studies involving Australian patients where available. Costs were reported in Australian dollars and adjusted to 2023 values. Background mortality data were obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics[21].

Australia has a universal healthcare system, and most cost estimates were derived from the Medicare Benefits Schedule and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, which list the government rebates for interventions and medicines[22,23].

Utilities ranged from zero (death) to one (perfect health). QALYs were calculated by multiplying the time spent in each health state by its corresponding utility weight.

Cost-effectiveness

Cost-effectiveness was calculated by dividing the incremental cost difference between two surveillance strategies by the corresponding difference in QALYs. A WTP threshold of A$50,000 per QALY was used to define cost-effectiveness, consistent with thresholds commonly applied in Australian cost-effectiveness studies.

Primary outcome of interest: (biomarker vs. US-AFP surveillance)

The primary purpose of our study was to determine the threshold price at which biomarker-based surveillance would be cost-effective compared with the current standard of care, US-AFP surveillance.

Comparison with no surveillance

We also determined the threshold price at which biomarker surveillance would be cost-effective compared with no surveillance. For US-AFP surveillance, we calculated the ICER relative to no surveillance.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted two types of sensitivity analyses. First, a two-way sensitivity analysis examined the impact of biomarker price and annual HCC incidence on cost-effectiveness, using a WTP threshold of A$50,000 and including all three surveillance strategies.

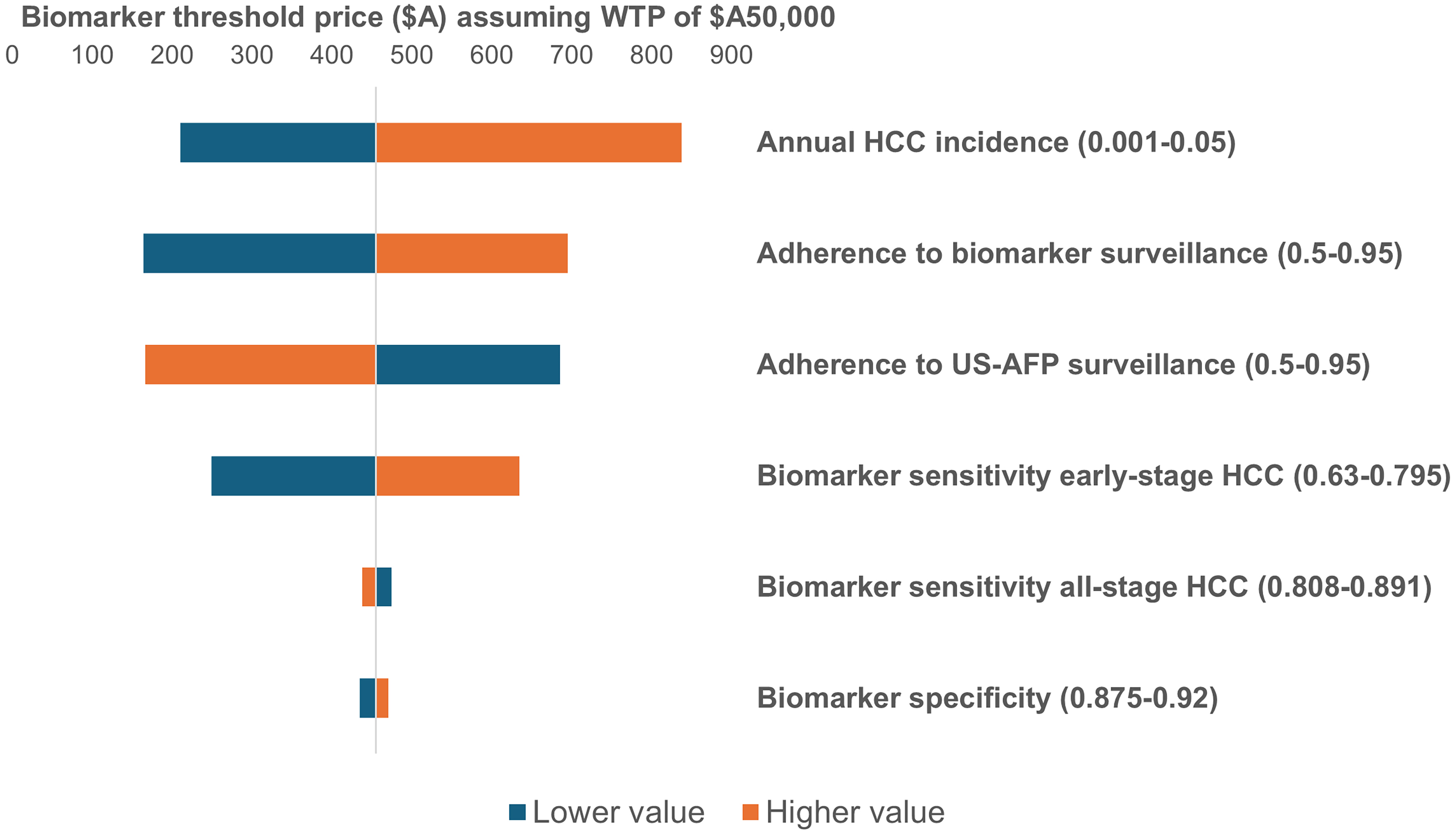

Second, a series of one-way sensitivity analyses was conducted on key parameters, presented in a tornado diagram. The outcome was the biomarker threshold price required to achieve cost-effectiveness at a WTP of A$50,000. Ranges for key parameters were based on 95% confidence intervals where available.

RESULTS

Model parameters and base-case analysis

The complete set of model parameters, sources, and assumptions is available in Supplementary Tables 1-5.

Base-case analysis

The base-case results are shown in Tables 1 and 2. US-AFP surveillance cost A$1,915 more than no screening. Compared with no screening, US-AFP surveillance provided a 0.04 QALY gain, while biomarker surveillance provided a 0.07 QALY gain. The ICER for US-AFP surveillance was A$43,397 relative to no surveillance, making it cost-effective at a WTP threshold of A$50,000.

Base-case analysis: US-AFP screening vs. no screening

| Cost (A$) | Incremental cost (A$) | QALYs | Incremental ∆ in QALYs | ICER (A$) | |

| No screening | 48,978.77 | - | 5.55 | - | - |

| US-AFP screening | 50,893.97 | 1,915.20 | 5.59 | 0.04 | 43,397.30 |

Base-case analysis: biomarker screening vs. US-AFP screening

| Cost (A$) | Incremental cost (A$) | QALYs | Incremental ∆ in QALYs | ICER (A$) | |

| US-AFP screening | 50,893.97 | - | 5.59 | - | - |

| Biomarker screening | 51,928.73* | 1,034.76 | 5.62 | 0.02 | 50,000* |

The cost of biomarker screening was determined by setting the biomarker price at the threshold required for cost-effectiveness (A$455 at a WTP of A$50,000). This resulted in a total cost of A$51,929, corresponding to an incremental cost of $1,035.

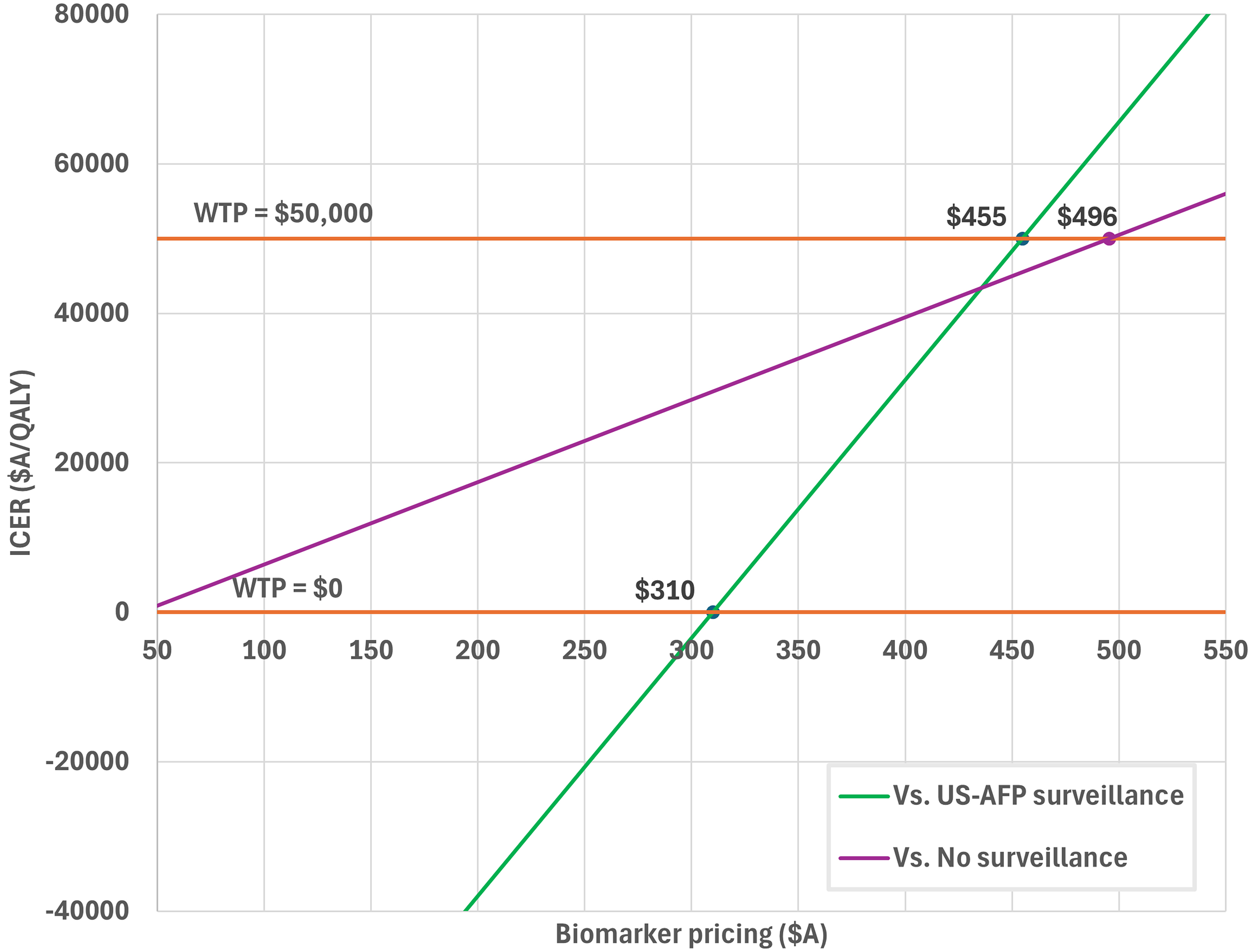

Primary outcome: threshold price for biomarker surveillance

The threshold price analysis for biomarker surveillance is presented in Figure 2. Biomarker surveillance was cost-effective compared with US-AFP surveillance if priced at ≤ A$455 (WTP A$50,000). At a price of ≤ A$310, biomarker surveillance dominated US-AFP surveillance (ICER A$0/QALY).

Figure 2. Price threshold analysis of Biomarker Panel-based HCC surveillance. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; US-AFP: ultrasound with alpha-fetoprotein; WTP: willingness-to-pay.

When compared with no surveillance, biomarker surveillance was cost-effective at prices up to A$496 (WTP A$50,000).

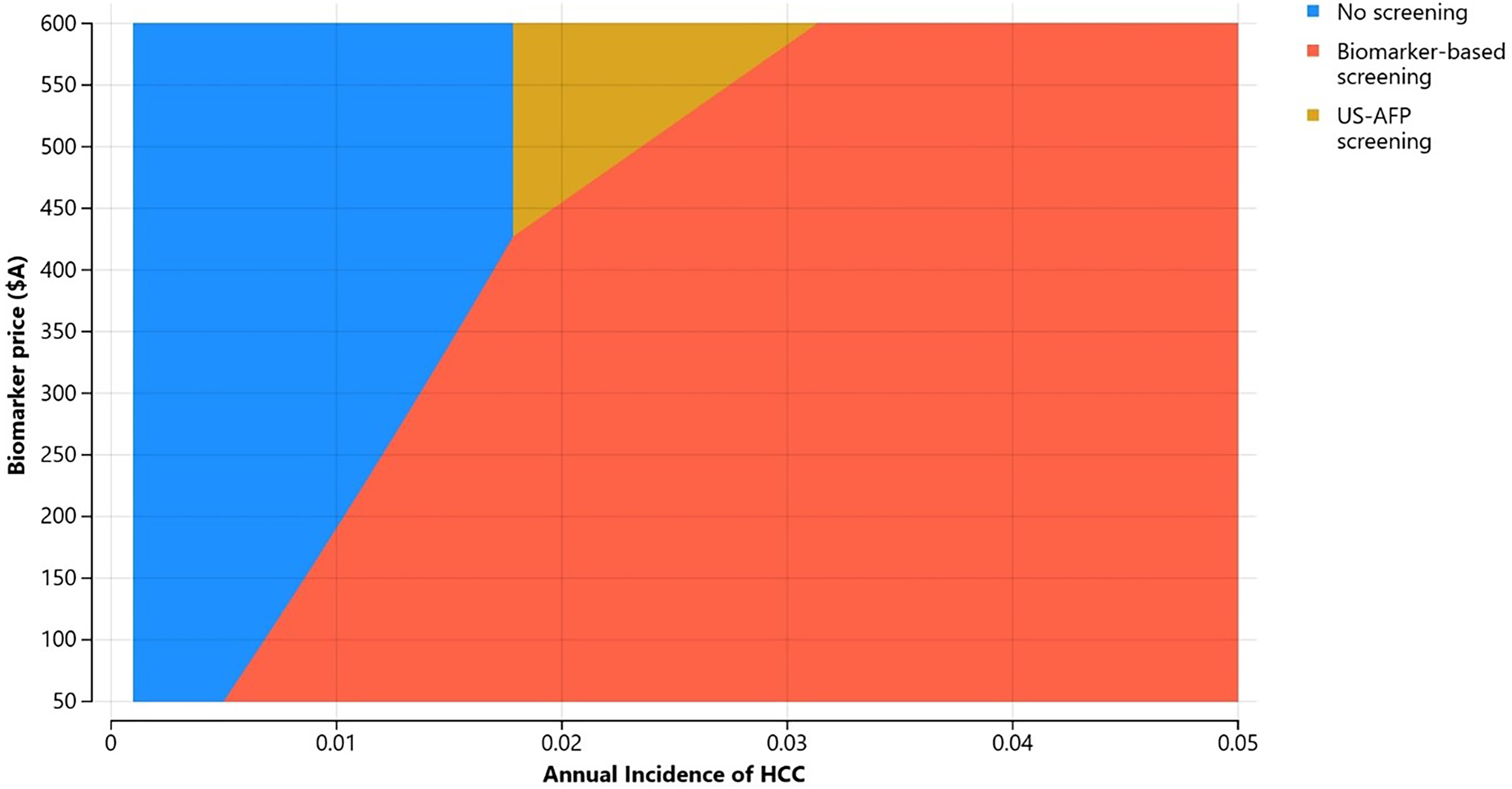

Two-way sensitivity analysis: biomarker price and annual incidence of HCC (all three scenarios)

Figure 3 presents a two-way sensitivity analysis varying biomarker price (A$50-600) and annual HCC incidence (0.1%-5%). In most scenarios, biomarker surveillance was the most cost-effective strategy, particularly when annual HCC incidence exceeded 1%. No surveillance was the preferred option only at very low HCC incidence rates. US-AFP surveillance was rarely the most cost-effective option, and only when biomarker prices were high (> A$435).

One-way sensitivity analyses

One-way sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the effect of key parameters on biomarker threshold pricing, summarized in the tornado diagram [Figure 4]. These parameters included biomarker test performance (sensitivity to early-stage HCC, sensitivity to all-stage HCC, specificity), adherence to each surveillance strategy, and annual HCC incidence. Biomarker threshold prices ranged from A$165 (biomarker surveillance adherence of 50%) to A$838 (annual HCC incidence of 5%).

Figure 4. Tornado diagram from one-way sensitivity analyses (biomarker surveillance vs. US-AFP surveillance). US-AFP: Ultrasound with alpha-fetoprotein; WTP: willingness-to-pay.

Higher HCC incidence, better adherence to biomarker surveillance, greater biomarker sensitivity for early-stage HCC, and higher biomarker specificity were all associated with higher threshold prices. Conversely, greater adherence to US-AFP surveillance and higher sensitivity of the biomarker for all-stage HCC were associated with lower threshold prices.

DISCUSSION

Recent validation studies have highlighted the considerable potential of novel biomarker panels for HCC surveillance in people with cirrhosis. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of these panels across diverse healthcare contexts is crucial for their successful adoption. Our analysis indicates that, within the Australian healthcare system, biomarker panel surveillance could be cost-effective, and even cost-saving, compared with US-AFP if delivered at plausible price points. In a two-way sensitivity analysis that incorporated HCC incidence and biomarker pricing, biomarker surveillance was the most cost-effective strategy in most scenarios, relative to US-AFP surveillance or no screening.

In our model, the advantage of biomarker panel surveillance was driven by its superior diagnostic performance compared with US-AFP. Specifically, we assumed higher sensitivity for early-stage HCC detection but lower sensitivity for detection across all stages, consistent with recent validation data for the GAAD panel[15]. Greater detection of early-stage tumors resulted in increased effectiveness at lower costs, as curative treatments are less expensive than non-curative therapies such as systemic therapy. This pattern is further reflected in our sensitivity analyses [Figure 4], where higher sensitivity for early-stage tumors was associated with an increased biomarker threshold price, whereas sensitivity across all stages lowered the threshold price.

Although no biomarker panels are currently available in Australia to enable accurate cost estimates, it is worth noting that most additional costs for the GAAD panel stem from the DCP biomarker and expenses related to the algorithm, as AFP is already widely available (priced at A$24). The GALAD panel would add both DCP and AFP-L3. For comparison, Singal et al. conducted an economic analysis in the United States using the GALAD score, modeling a biomarker panel cost of US$200[19]. In that analysis, cost-effectiveness was achieved at a WTP threshold of US$150,000.

Biomarker-based surveillance may also generate unmodeled cost savings relative to US-AFP. Ultrasound is more time-consuming than blood collection, requiring participants to spend additional time away from work, education, and other activities. This burden becomes particularly relevant in the context of lifelong surveillance with a biannual schedule. Such indirect costs were not incorporated in our modeling, which aligns with the standard approach in Australian cost-effectiveness analyses, given the lack of robust and generalizable data. Excluding these costs therefore represents a conservative modeling choice.

Serum biomarker surveillance may also offer greater accessibility than ultrasound, which could improve real-world cost-effectiveness. Surveillance uptake is a well-recognized limitation of US-AFP, with a prior meta-analysis reporting an overall adherence rate of 52%[24]. True adherence may be even lower, with retrospective studies showing rates of 39%, likely better reflecting real-world practice[24]. In Australia, surveillance uptake of over 80% has been reported in people attending tertiary gastroenterology services[25,26], whereas markedly lower rates have been documented in patients managed solely in primary care[27]. In our baseline model, we assumed no difference in uptake between US-AFP and biomarker panel surveillance. However, in some contexts, such as regional and remote regions, biomarker panels could enhance participation and therefore overall cost-effectiveness. In our one-way sensitivity analysis, if adherence to US-AFP remained at 70% but adherence to biomarker surveillance increased to 95%, the biomarker threshold price would rise to A$695.

The epidemiology of cirrhosis is evolving, with MASLD and ARLD becoming increasingly prevalent in many developed countries[3]. This growing at-risk population places substantial demand on surveillance resources. Ultrasound, in particular, is a limited resource in strained healthcare systems. Recently, one Australian study reported a tenfold increase in demand for ultrasound-based HCC surveillance between 2013 and 2023[28]. Such growth threatens the long-term feasibility of biannual US-AFP surveillance for people with cirrhosis and creates opportunity costs for other patients requiring radiology and ultrasound services.

Limitations

As this study is based on an economic model that incorporates several assumptions, our results provide only an estimate of the threshold price at which biomarker panels could achieve cost-effectiveness. The actual cost-effectiveness will vary depending on a range of patient- and system-level factors, including adherence to HCC surveillance and the incidence of HCC in the surveyed population. Additionally, the diagnostic performance of the GAAD algorithm is derived from the results of a promising phase 3 study[15]. However, long-term phase 4 data are still required to validate these findings, particularly in the Australian context. This uncertainty is highlighted in our one-way sensitivity analyses, illustrated in the tornado diagram. The validity of our HCC surveillance modeling is supported by its comparability to other Australian economic modeling studies[17,29]. Notably, we found US-AFP to be cost-effective, with an ICER of A$43,397 reported in our study.

Our model did not account for real-world regulatory, infrastructural, or equity-related considerations that may affect the implementation of biomarker panel-based surveillance in Australia. These factors warrant further investigation prior to clinical adoption to fully realize the potential benefits of biomarker-based surveillance suggested by our results.

Conclusion

Novel biomarker panels represent a promising strategy for HCC surveillance in people with cirrhosis. Our economic modeling, conducted within the Australian universal healthcare context, suggests that biomarker panel surveillance would be cost-effective if priced below A$455 and dominant if priced below A$310. Compared with the current standard of care, biomarker-based HCC surveillance in Australia is therefore likely to be cost-effective and potentially even cost-saving. Its implementation as a critical cancer screening tool merits consideration, particularly given its potential to improve the accessibility and uptake of HCC surveillance, pending further real-world validation.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, writing - original draft preparation: Hui S

Methodology, writing - review and editing: Irving A

Writing - review and editing: Le S, Dev A

Conceptualization, writing - review and editing: Bell S

Availability of data and materials

The model parameters and Markov model are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Financial support and sponsorship

Hui S is supported by a Research Training Program stipend as part of his PhD studies.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-49.

2. Hong TP, Gow P, Fink M, et al. Novel population-based study finding higher than reported hepatocellular carcinoma incidence suggests an updated approach is needed. Hepatology. 2016;63:1205-12.

3. Huang DQ, Terrault NA, Tacke F, et al. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis - aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:388-98.

4. Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182-236.

5. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723-50.

6. Omata M, Cheng AL, Kokudo N, et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 2017 update. Hepatol Int. 2017;11:317-70.

7. Lubel JS, Roberts SK, Strasser SI, et al. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a consensus statement. Med J Aust. 2021;214:475-83.

8. Hong TP, Gow PJ, Fink M, et al. Surveillance improves survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective population-based study. Med J Aust. 2018;209:348-54.

9. Singal AG, Zhang E, Narasimman M, et al. HCC surveillance improves early detection, curative treatment receipt, and survival in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2022;77:128-39.

10. Hui S, Bell S, Le S, Dev A. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in Australia: current and future perspectives. Med J Aust. 2023;219:432-8.

11. Parikh ND, Tayob N, Singal AG. Blood-based biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma screening: approaching the end of the ultrasound era? J Hepatol. 2023;78:207-16.

12. Liebman HA, Furie BC, Tong MJ, et al. Des-gamma-carboxy (abnormal) prothrombin as a serum marker of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1427-31.

13. Taketa K, Endo Y, Sekiya C, et al. A collaborative study for the evaluation of lectin-reactive alpha-fetoproteins in early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5419-23.

14. Li C, Zhang Z, Zhang P, Liu J. Diagnostic accuracy of des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin versus α-fetoprotein for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:E11-25.

15. Piratvisuth T, Hou J, Tanwandee T, et al. Development and clinical validation of a novel algorithmic score (GAAD) for detecting HCC in prospective cohort studies. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7:e0317.

16. Parikh ND, Singal AG, Hutton DW, Tapper EB. Cost-effectiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: an assessment of benefits and harms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1642-9.

17. Nguyen ALT, Si L, Lubel JS, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance based on the Australian Consensus Guidelines: a health economic modelling study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:378.

18. Nan Y, Garay OU, Lu X, et al. Early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma screening in patients with chronic hepatitis B in China: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Comp Eff Res. 2024;13:e230146.

19. Singal AG, Chhatwal J, Parikh N, Tapper E. Cost-effectiveness of a biomarker-based screening strategy for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Cancer. 2024;13:643-54.

20. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al; CHEERS Task Force. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ. 2013;346:f1049.

21. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Provisional Mortality Statistics. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/provisional-mortality-statistics/latest-release. [Last accessed on 5 Sep 2025].

22. Department of Health and Aged Care Australian Government. MBS Online. Available from: https://www.mbsonline.gov.au/. [Last accessed on 5 Sep 2025].

23. Department of Health and Aged Care Australian Government. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). Available from: https://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/home. [Last accessed on 5 Sep 2025].

24. Zhao C, Jin M, Le RH, et al. Poor adherence to hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of a complex issue. Liver Int. 2018;38:503-14.

25. Low ES, Apostolov R, Wong D, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance and quantile regression for determinants of underutilisation in at-risk Australian patients. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13:2149-60.

26. Hui S, Sane N, Wang A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in the telehealth era: a single-centre review. J Telemed Telecare. 2025;31:64-72.

27. Allard N, Cabrie T, Wheeler E, et al. The challenge of liver cancer surveillance in general practice: do recall and reminder systems hold the answer? Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:859-64.

28. Coombs PR, Chen J, Curry GJ, et al. Sonography in a large Australian public ultrasound service: 10 years of change and innovation. Sonography. 2024;11:169-76.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].