Multicomponent porous metal oxide semiconductors for advanced gas sensing

Abstract

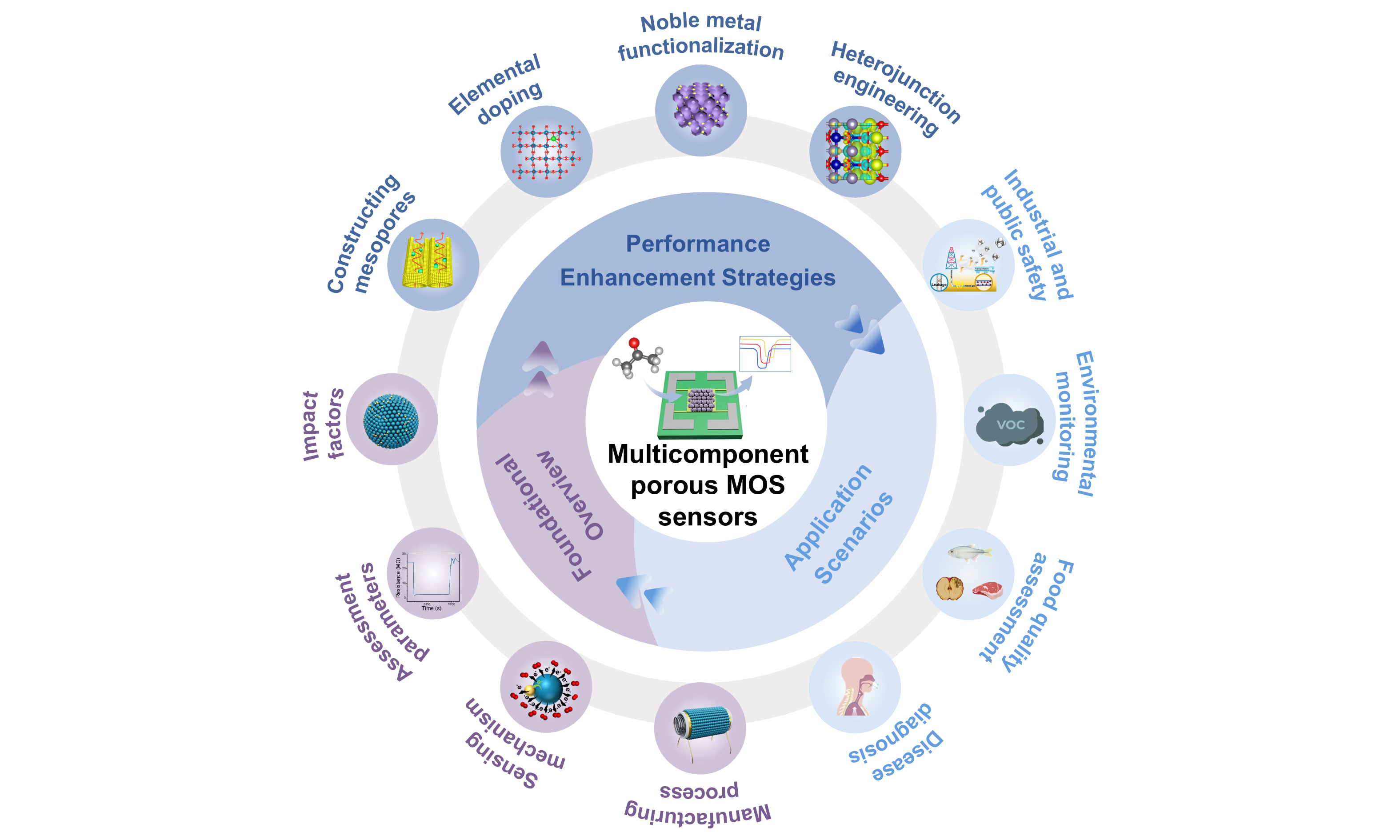

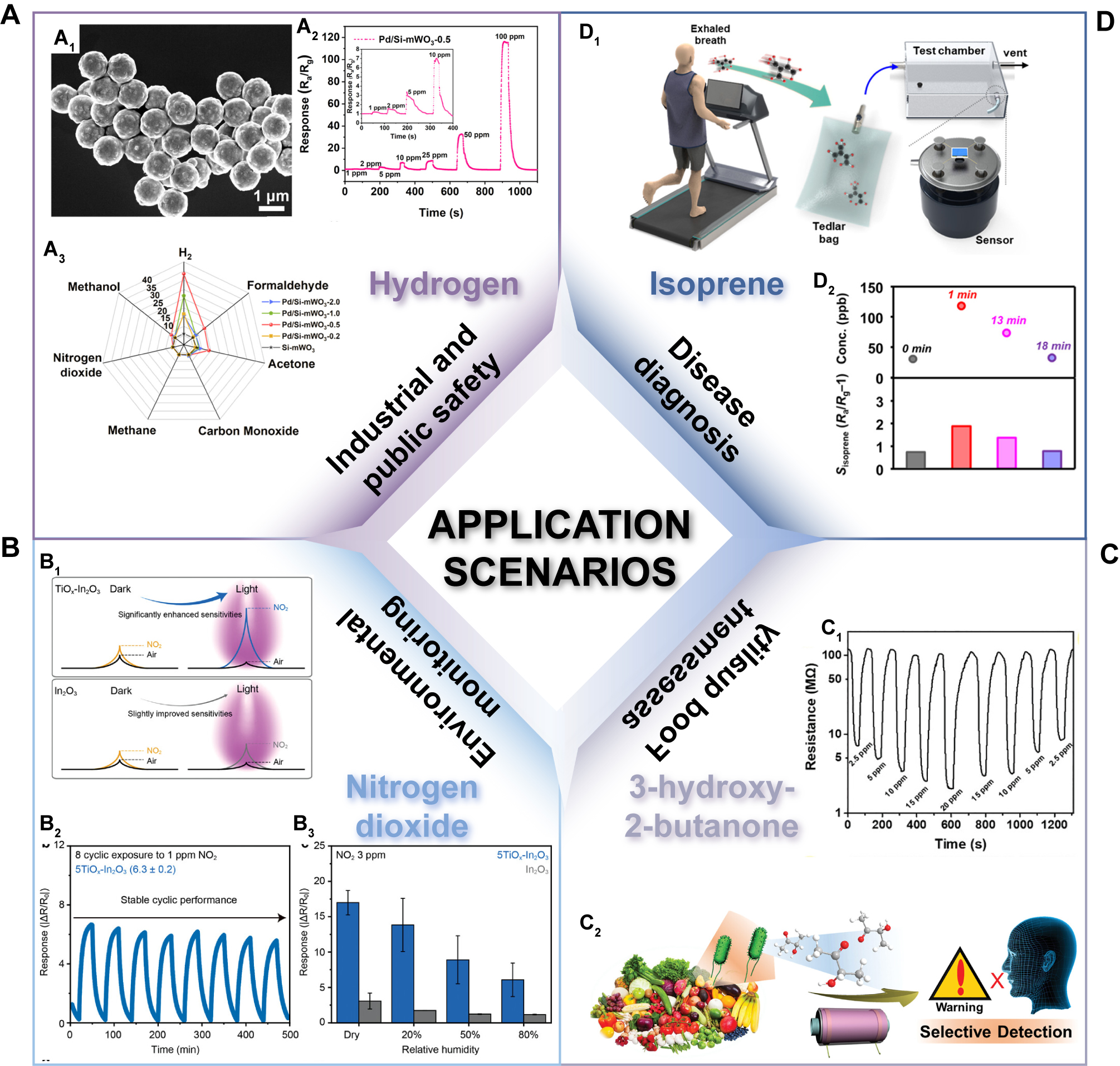

Rapid advances in sensing technologies are transforming how humans monitor and interact with their surroundings, driving progress in fields spanning environmental protection, industrial safety, healthcare, food quality control, and intelligent living systems. Within this technological landscape, metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) sensors have emerged as a particularly promising platform, offering high sensitivity, fast response, low cost, and facile integration into diverse device architectures. Recent years have witnessed rapid progress in multicomponent porous MOS sensors, which leverage synergistic effects between different components and hierarchical porous architectures to achieve superior sensing performance. This review provides a comprehensive overview of multicomponent porous MOS gas sensors, encompassing fundamental sensing mechanisms, performance evaluation parameters, and fabrication processes. Particular emphasis is placed on advanced strategies for performance enhancement, including the construction of mesoporous architectures, elemental doping, noble metal functionalization, and heterojunction engineering. Furthermore, recent progress in practical applications is summarized, covering industrial and public safety, environmental monitoring, food freshness evaluation, and disease diagnosis. Finally, future development trends and critical challenges are discussed, highlighting opportunities in high‐throughput synthesis, machine learning‐assisted material design, low‐temperature flexible sensing, multi-parameter intelligent detection, and scalable device integration. This review aims to provide a systematic framework and forward‐looking perspective to inspire the rational design and technological advancement of next‐generation multicomponent MOS gas sensors.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In the era of artificial intelligence (AI) and the internet of things, sensor technologies play a pivotal role as essential bridges connecting the material world with human society. Mimicking human sensory organs, modern sensors gather and convey information across multiple spatial scales, significantly extending our capacity to sense and interpret the environment. They have become powerful tools for exploring and transforming nature, driving technological innovation, and supporting societal development.

As a key branch of sensor technology, gas sensors have found widespread applications in diverse fields including disease diagnosis[1,2], environmental monitoring[3], food quality control[4], and industrial safety assurance[5,6]. In recent years, their applications have further expanded into emerging domains including intelligent healthcare and elderly care[7,8], aerospace and military areas[9], and battery safety in electric vehicles[10], as well as various AI-driven monitoring systems[11-13]. Over the past decades, various types of gas sensors have been developed, such as catalytic combustion sensors, electrochemical sensors, thermal conductivity sensors, infrared absorption sensors, paramagnetic sensors, solid electrolyte sensors, and metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) sensors[14]. Among these, MOS sensors have attracted particular attention due to their high sensitivity, fast response, low cost, compact size, and facile fabrication and integration, making them one of the most extensively studied and applied sensor technologies[15-17].

Driven by advances in materials chemistry and nanotechnology, MOS gas sensors have undergone significant evolution, enabling improved sensitivity, selectivity, stability, and response speed. In particular, the integration of multiple components and the construction of porous architectures have emerged as powerful strategies to enhance sensing performance[18-20], meeting the increasing demands of complex application scenarios. The incorporation of dopants, noble metals, or secondary oxides provides a versatile means to tailor electronic structures, defect chemistry, catalytic properties, and surface adsorption behavior[21,22]. Meanwhile, introducing mesoporosity offers high surface areas, abundant accessible active sites, and efficient gas diffusion pathways, which are essential for rapid and sensitive detection[23,24]. Despite rapid progress, the field is now confronted with the challenge of rationally integrating these design strategies to achieve controllable architectures and optimized sensing functions in a systematic manner.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent developments in multicomponent porous MOS gas sensors. First, the fundamental aspects of MOS gas sensors, including device fabrication, sensing mechanisms, and performance evaluation metrics, are introduced to provide the necessary background. Next, various performance enhancement strategies are systematically classified and discussed, including mesoporous structure construction (hard-template method, soft-template method, and self-templating method), elemental doping (rare-earth elements, transition-metal elements, and non-metal elements), noble metal modification, and heterojunction engineering (p-n, p-p, and n-n junctions). Special attention is given to how these strategies influence structural features, electronic properties, and surface reactions. Finally, the diverse applications of multicomponent MOS gas sensors in industrial and public safety, environmental monitoring, food quality assessment, and disease diagnosis are summarized. By systematically integrating recent advances in multicomponent design and mesostructure engineering, this review establishes a clear framework for understanding the structure-property-function relationships that govern sensing performance. We also outline current challenges and future research directions, aiming to inspire further innovation towards the rational design of next-generation high-performance MOS gas sensors.

OVERVIEW OF METAL OXIDE SEMICONDUCTOR GAS SENSORS

Manufacture of MOS sensors

The most commonly employed sensor device is the chemiresistive gas sensor manufactured from ceramic tubing. Its structure comprises a porous laminate of sensing material, a heater, and a resistance measurement element (typically a pair of metal electrodes). The manufacturing process comprises several steps. First, a sintered ceramic tube with a gold electrode and platinum wire is prepared. Next, a nickel-chromium alloy coil is inserted into the ceramic tube to serve as a heater for controlling the sensor’s operating temperature. Finally, a uniform coating of sensitive material is deposited onto the surface of the alumina ceramic tube. The manufacture of high-quality gas sensors typically commences with the wet process for preparing fine MOS powder. For instance, in a mesoporous zinc oxide (mZnO)-based sensor, the material is lightly milled to a microcrystalline size of approximately 10 nm[25]. This is then suspended in deionized water within an agate mortar to form a slurry. Subsequently, the slurry is coated onto the ceramic tube surface to form a thick film, with a nickel-chromium alloy coil positioned inside the tube as a heater. To enhance sensor stability prior to testing, the prepared sensor is aged for one week at its optimum operating temperature. The assembled device is illustrated in Figure 1A. The static gas distribution method is employed to test gas response. Within the circuit measuring gas response [Figure 1B], the load resistor (RL) is connected in series with the gas sensor to maintain the voltage across the sensor within its optimal range. The circuit voltage (VC) is set to 5 V, with the output voltage (Vout) representing the load voltage across the load resistor. In a typical sensing process, the test gas is first introduced into the test chamber, where its concentration is adjusted through air dilution. Subsequently, the test gas reacts chemically with oxygen molecules adsorbed on the sensing layer, releasing free electrons. This process causes a decrease in the sensor’s resistance and voltage, leading to an increase in Vout. Figure 1C illustrates the schematic structure of the developed mZnO-based gas sensor.

Figure 1. (A) Assembled ceramic tube device; (B) Gas sensing measurement circuit; (C) Structural schematic of the bypass-heated mZnO-based ceramic tube sensing device. Figure A-C is quoted with permission from Zhou et al.[25]; (D) Schematic diagram of MEMS sensor and its spatial structure; SEM image of the central region of the MEMS chip. Figure 1D is quoted with permission from Yan et al.[26]. mZnO: Mesoporous zinc oxide; MEMS: microelectromechanical system; SEM: scanning electron microscope.

As a miniaturized version of ceramic tube devices, microelectromechanical system (MEMS)-based sensors developed in recent years have garnered significant attention. Various types of MOS sensors fabricated using MEMS technology offer numerous advantages, including compact size, light weight, superior performance, ease of mass production, and low cost. Consequently, numerous studies have commenced employing MEMS technology to manufacture diverse gas sensors. Figure 1D presents a schematic diagram and scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the MEMS sensor device[26]. Zhu et al. demonstrated a novel self-heating MEMS sensor featuring heterostructured p-CuO/n-SnO2 core-shell nanowires, exhibiting outstanding gas sensing performance towards formaldehyde[27]. The specific fabrication process involves the following steps. First, the prepared p-CuO/n-SnO2 sensing material is uniformly dispersed in deionized water, and then dropped onto the MEMS heating device. After sufficient drying at room temperature, the MEMS device containing the sensitive material was placed in a 45 °C oven for 24 h. Subsequently, the fabricated MEMS device was connected to the external circuit via aluminum wire bonding. Guo et al. prepared three-dimensional (3D) CuO/WO3 hierarchical hollow microspheres assembled from irregular nanosheets (NSs) via ultrasonic wet chemical etching and pyrolysis, and fabricated MEMS sensors based on this material[28]. Compared to the pristine WO3 sensor, the CuO/WO3 sensor exhibited enhanced xylene gas sensing properties, including faster response and recovery, higher sensitivity, good selectivity, and long-term stability. The favorable sensing characteristics of the CuO/WO3 MEMS sensor can be attributed to its unique 3D hierarchical structure and p-n heterojunctions. Wang et al. employed a template-free ultrasonic spray pyrolysis method to synthesize Co-doped In2O3 (Co-In2O3) exhibiting a hollow porous microstructure and abundant active adsorption sites[29]. The resulting Co-In2O3-based toluene sensor, utilizing MEMS technology, enabled operation under conditions of several tens of milliwatts of power.

For MOS as a sensing material, the adoption of MEMS-based microheater devices offers numerous advantages. Firstly, the compact dimensions of such devices enable device miniaturization, thereby enhancing the flexibility and applicability of the sensor. Secondly, the low power consumption of MEMS microheater devices helps extend sensor lifespan and reduce energy expenditure. Thirdly, the easily adjustable temperature of this device enables precise control over the operating temperature of sensors, thereby enhancing their stability and repeatability. Consequently, the MEMS-based microheater device is expected to become the preferred technology for future MOS gas sensors.

Sensing mechanism of MOS sensors

Based on their dominant charge carriers, MOS can be categorized into n-type (where the charge carriers are electrons) and p-type semiconductors (where the charge carriers are holes). For instance, metal oxides including WO3, ZnO, In2O3, SnO2, Fe2O3, TiO2, and MoO3 belong to n-type semiconductors, whereas Co3O4, NiO, CuO, Cu2O, Mn3O4, and Cr2O3 are classified as p-type semiconductors[30]. The sensing mechanisms vary depending on the intrinsic properties of the materials. With the widespread application and in-depth research of gas sensors, discussions on sensing mechanisms have also increased. Scientists have attempted to construct more reasonable and universal theoretical models to explain the MOS sensing mechanism. Researchers have analyzed and interpreted data from multiple perspectives, uncovering numerous distinct mechanisms, including the most prevalent electron depletion layer (EDL) theory[31], hole accumulation layer (HAL) theory[32], bulk resistance control mechanism[33], and gas diffusion control mechanism[34]. These theories encompass certain gas sensing mechanisms within corresponding materials, though significant overlaps exist between them.

Electron depletion layer theory and hole accumulation layer theory

For chemiresistive MOS sensors, the sensing mechanism is primarily attributed to electrical signal changes induced by gas adsorption and desorption. At the microscopic level, when MOS materials are exposed to air, oxygen molecules adsorb onto the surface of the sensing material by capturing electrons from the conduction band, subsequently ionizing into chemically adsorbed oxygen species (such as O2-, O-, or O2- ions). The type of chemically adsorbed oxygen is strongly dependent on the operating temperature (T). At relatively low temperatures (T < 150 °C), O2- is the predominant oxygen species. Between 100 and 300 °C, O- ions are primarily adsorbed onto the MOS surface. At higher temperatures (T > 300 °C), the O2- species become dominant. The formation process of oxygen species can be summarized by[35,36]:

Meanwhile, an EDL with higher resistance than the core region forms on the surface of n-type MOS, or a HAL with lower resistance than the core region forms on the surface of p-type MOS. This results in an increase (or decrease) in the resistance of the n-type (or p-type) MOS. When MOS materials are exposed to an atmosphere containing target gases, redox reactions occur between gas molecules and chemically adsorbed oxygen species. This further results in the release of electrons back into the conduction band of the MOS (for reducing gases) or the capture of additional electrons from the MOS (for oxidizing gases). Accordingly, the thickness of the EDL (or HAL) and the resistance of the MOS change. For instance, when n-type MOS material is exposed to reducing gases (such as acetone), the thickness of the EDL decreases, consequently reducing the resistance of the n-type MOS material [Figure 2A][37]. Conversely, when oxidizing gases are introduced, both the EDL thickness and the resistance of the n-type MOS further increase. For p-type MOS materials, when reducing gases (such as acetone) are introduced, the resistance increases due to the recombination of released electrons and holes, resulting in a decrease in HAL thickness [Figure 2B]. This behavior is the opposite of that observed when oxidizing gases are introduced[38]. Following these processes, the resistance of the MOS material undergoes significant changes, exhibiting a pronounced response to the target gas.

Figure 2. (A) Schematic of the electron depletion layer theory. Mechanistic representation of acetone sensing by an n-type MOS sensor (A1); Initial electronic levels (A2); Changes in the electronic levels of n-type MOS upon exposure to oxygen (A3) and target gases (A4). Figure 2A is quoted with permission from Panigrahi et al.[37]; (B) Core-shell configuration of p-type MOS in vacuum and air (B1); Interaction of p-MOS in the presence of reducing gas CO (B2) and in oxidizing NO2 (B3). Figure 2B is quoted with permission from Kaur et al.[38]; (C) Schematic illustration of gas diffusion processes at different pore sizes; (D) Schematic representation of gas diffusion processes within hollow tin dioxide microspheres at different temperatures. Figure 2C and D is quoted with permission from Wang et al.[34]. MOS: Metal oxide semiconductor.

Bulk resistance control mechanism

The bulk resistance control mechanism fundamentally relies on the resistance variation of the MOS sensors originating from phase transitions within the sensitive materials. The mechanism has a relatively limited applicability, and is only suitable for analyzing gas sensing processes involving γ-Fe2O3 and perovskite-type metal oxides (ABO3), where ABO3 denotes the general chemical formula of perovskite structures.[30]. Wang et al. developed Fe2O3 sensors with distinct α-Fe2O3 and γ-Fe2O3 phase compositions by heating Fe-metal-organic framework (MOF) templates, and analyzed the differing gas sensing mechanisms of the two iron oxides[39]. α-Fe2O3 possesses a relatively stable phase structure, and its sensing mechanism can be explained by a typical oxygen adsorption model. However, the resistance change in γ-Fe2O3 is primarily attributed to alterations in its internal phase structure. γ-Fe2O3 features an inverse spinel structure, wherein the octahedral voids (Fe2+ and half Fe3+ ions) typically feature a vacant cation site (□) to compensate for the increased positive charge. When exposed to a reducing gas environment, the Fe3+ ions within the octahedral sites are reduced to Fe2+, causing the material to transform into Fe3O4. Owing to the existence of the (Fe2+-Fe3+-Fe2+-Fe3+) structure within Fe3O4, electron migration becomes significantly facilitated, resulting in a material whose resistivity is ten orders of magnitude smaller than that of γ-Fe2O3. Upon re-exposure to air, Fe3O4 re-oxidizes to γ-Fe2O3, with its electrical resistance increasing accordingly. It should be noted that the redox reactions occurring during gas sensing are reversible, involving only simple phase transitions without any crystal structure transformation. These mechanisms are expressed as[40,41]:

where Th denotes the tetrahedral interstitial, □ represents a cation vacancy, Oh signifies the octahedral interstitial, and x is the reduction degree of Fe3+.

Gas diffusion control mechanism

In gas sensing processes, two key components are typically involved: the sensitive material and the target gas. The aforementioned EDL, HAL and bulk resistance control mechanisms primarily focus on the physical and chemical properties of the sensing materials, whereas the gas diffusion control mechanism places greater emphasis on the transport behaviors of the gas within sensing materials. The most significant factor influencing gas diffusion is the material morphology. As early as the 1990s, scientists proposed the theory that gas diffusion governs the sensitivity of MOS sensors[42-44]. Indeed, this theory serves as a complement to the former two mechanisms, offering a more comprehensive explanation for the variations in physical parameters during gas sensing. By studying the diffusion process of gases through material surfaces, we can gain deeper insights into the operating principles of gas sensors and provide theoretical guidance for designing and optimizing novel intelligent sensors.

Wang et al. constructed pore channel models through research on SnO2 microspheres, comprehensively explaining the relationship between surface chemical reactions (SCR) and gas diffusion, along with their impact on gas sensing performance. Based on Knudsen diffusion theory and reaction kinetics, the gas diffusion rate (Dk) and SCR rate (k) are respectively expressed by[34]

where r denotes the pore radius, R is the gas constant (8.314 J·mol-1·K-1), T represents the temperature, M is the molecular weight, A is the pre-exponential factor, and Ea denotes the activation energy. Based on the two equations, k is primarily determined by T. At low temperatures (T < 180 °C), the SCR rate is relatively low, making it the rate-determining step controlling the overall reaction. Furthermore, the entire process occurs on the surface, with the external surface area the primary factor controlling gas sensing performance. At elevated temperatures (T > 260 °C), the increase in Dk is less pronounced than that of k, rendering the process diffusion-controlled, in which pore size exerts a more significant influence on gas sensing performance. At intermediate temperatures (180 °C ≤ T ≤ 260 °C), gas diffusion and SCR compete in equilibrium, with the entire system operating under dual control. Overall, as temperature increases, diffusion control progressively supplants SCR control. Based on this, this work proposes a pore channel model to analyze the diffusion of gas molecules [Figure 2C]. At low temperatures (T < 180 °C), the mean free path of gas molecules exceeds the pore diameter, thereby impeding their diffusion into the channels and causing most responses to occur outside the channels. Although both diffusion and SCR rates are relatively low, the SCR rate plays a decisive role. As temperature increases, the mean free path of gas molecules gradually diminishes to match the pore size, enabling more molecules to diffuse into the pore channels and react with oxygen species, forming a transition state. At high temperatures (T > 260 °C), the mean free path becomes shorter than the pore diameter, enabling greater molecular diffusion. However, the increase in k value far exceeds the Dk value, ultimately leading to the emergence of a diffusion-controlled state. To further elucidate gas sensing behaviors, the authors developed a hollow sphere (HS) model to describe the interplay between SCR and gas diffusion [Figure 2D]. At low temperatures (T < 150 °C), the oxygen species adsorbed on the SnO2 surface are predominantly less reactive O2-, rendering SCR inactive and thus limiting the gas sensing reactions. A portion of the target gas undergoes partial oxidation on the outer surface, while the residual gas diffuses into the pore interior to perform chemical reactions, including partial oxidation, complete oxidation, and ionization of minor oxidation products. In this case, gas diffusion progressively becomes the rate-determining step. Although the gas diffusion control mechanism requires further quantitative analysis and optimization of multiple factors, it has been extensively applied to evaluate the effect of morphology on the sensing performance of MOS materials. A detailed discussion on the construction and regulation of mesoporous architectures, including pore size, morphology and hierarchical design, will be presented in Section Constructing mesoporous metal oxides.

Assessment parameters of MOS sensors

The performance of MOS sensors can be evaluated using a variety of parameters, including but not limited to sensitivity, selectivity, response/recovery times, stability, reversibility, optimal operating temperature, detection limit, and manufacturing cost.

Sensitivity

Sensitivity (S) is one of the key indices for evaluating sensor performance, reflecting the response capability of the sensing material towards the target gas. For chemiresistive gas sensors, the output is the response value (R), defined as the ratio of the sensor’s resistance under the target gas atmosphere to its resistance in air. Taking reducing gases as an example, for n-type semiconductors, R = Ra/Rg; whereas for p-type semiconductors, R = Rg/Ra, where Ra denotes the sensor’s resistance in air, and Rg represents the sensor’s resistance in the target gas. The situation is reversed for oxidizing gases. The distinction between sensitivity and response is not always clear-cut, as both describe the extent of resistance variation. Sensitivity (S) can be expressed in alternative ways:

ΔR denotes the difference between Ra and Rg.

Selectivity

Selectivity refers to a gas sensor’s ability to accurately identify specific gases in the presence of mixed gases. Traditionally, selectivity is defined as the ratio of the sensor’s response towards the target gas to its response towards interfering gases[45]. This implies that the sensor should exhibit a distinctive response solely to the target gas, without interference from other gases. In practical applications, gas sensors often operate within complex working environments, where numerous interfering gas molecules are present during detection. Achieving selective detection of specific gases in mixed atmospheres is paramount, directly influencing the reliability and accuracy of sensors in real-world scenarios. Enhancing selectivity thus represents a significant research focus in gas sensor design and deployment.

Response/recovery time

Response and recovery times are crucial metrics for evaluating sensor performance, indicating how quickly the sensor’s signal rises upon exposure to the target gas and returns to baseline once the gas is removed. Response time (tres) and recovery time (trev) are defined as the times required for a gas sensor to achieve a 90% change in resistance following gas introduction or removal, respectively[46]. In practical applications, shorter response and recovery times indicate that sensors can respond rapidly to gas changes and return quickly to their original state, thereby ensuring the promptness and accuracy of monitoring. Therefore, optimizing response and recovery kinetics is crucial for achieving efficient gas detection, particularly in applications requiring timely responses, such as industrial safety monitoring. Generally speaking, sensing materials with higher porosity possess more gas diffusion pathways, allowing gas molecules to penetrate the material interior more readily, thereby facilitating the rapid response and recovery[47,48].

Stability

Stability refers to the ability of a gas sensor to maintain a consistent and stable signal output after prolonged operation. This is influenced by multiple factors, including material composition, ambient humidity, and operating temperature. The stability of a sensor is one of its most crucial characteristics in practical applications, as it directly influences the sensor’s reliability and lifetime. During prolonged operation, poor sensor stability may result in fluctuating or erroneous output signals, thereby diminishing the reliability and usability. Consequently, when designing and selecting sensors, it is essential to thoroughly consider and enhance their stability to ensure long-term, consistent operation under varying environmental conditions and to deliver accurate and dependable gas detection results.

Reversibility

Reversibility denotes the ability of a gas sensor to restore its baseline state once the target gas concentration returns to normal levels. This property is essential for ensuring reliable and stable sensor operation over time. Inadequate reversibility can cause cumulative measurement errors and undermine detection accuracy, thereby affecting both operational continuity and precision. Therefore, reversibility serves as a key criterion for evaluating sensor performance and practical applicability.

Optimum operating temperature

The optimum operating temperature is defined as the temperature at which a sensor achieves its maximum response to a given gas concentration. At this point, both sensitivity and response dynamics are optimized, enabling accurate and rapid target gas detection. In practice, operating temperatures should be kept as low as possible, since elevated temperatures increase fabrication and energy costs and may induce material degradation or unstable sensing behaviors. Therefore, determining the optimum operating temperature requires a careful balance between performance, energy efficiency, material stability, and practical application demands.

Detection limit

The limit of detection (LOD) is the lowest concentration of a target gas that can be reliably distinguished from the blank under defined conditions, commonly using an S/N (Singal/Noise) ≈ 3 or 3σ criterion. In practice, the LOD is obtained from the calibration curve as LOD = 3σ/m, where m is the slope and σ is the standard deviation of the blank (or replicate low-level measurements). A lower LOD indicates superior detectability at trace levels and is critical for high-sensitivity applications. For example, food spoilage releases marker gases such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S) at parts-per-billion (ppb) concentrations[49], whereas breath biomarkers for early disease screening (e.g., acetone) often occur at parts-per-million (ppm) to ppb levels[50]. Accordingly, achieving low detection limits has substantial practical significance.

Impact factors on MOS sensors’ performance

The performance of gas sensors is primarily determined by several key factors, including the composition, microstructure and grain size of the sensing material.

Composition

Different MOS materials exhibit distinct intrinsic characteristics, including surface properties, carrier concentration, defect types, terminal groups, bandgap, and electronic structure. These factors influence gas-solid interactions in different ways, thereby governing gas sensing performance[51,52]. Rational design and selection of appropriate material systems are therefore essential for achieving high sensitivity and selectivity. In gas sensing, n-type MOS (e.g., WO3, In2O3, SnO2, ZnO) are generally preferred over p-type counterparts[53]. Typically, n-type MOS show more pronounced resistance variations upon gas adsorption, which is attributed to their higher density of grain boundaries[54]. In contrast, p-type MOS usually display weaker resistance changes because parallel conduction pathways at interparticle interfaces diminish the overall modulation effect. Moreover, the sensitivity of p-type MOS sensors has been shown to scale only with the square root of that of n-type MOS sensors[55]. Despite this limitation, many p-type MOS materials, such as CuO, NiO, and Co3O4, remain widely used owing to their excellent catalytic activity[54-56-60]. For materials with wide band gaps, inter-band electron hopping becomes difficult, resulting in smaller resistance changes upon gas adsorption. Conversely, materials with narrow band gaps possess intrinsically high carrier concentrations, which reduce the relative modulation induced by adsorption, often leading to negligible signal changes. Finally, regardless of whether n-type or p-type MOS are employed, single-component materials often suffer from limited sensitivity and severe cross-sensitivity. The synergistic combination of multiple metal oxide components may also induce interfacial interactions, whose detailed roles, including heterojunction formation and interfacial charge modulation, will be systematically discussed in Section Heterojunction engineering.

Microstructure

The electrical and chemical properties of sensing materials can be tuned by tailoring their microstructural morphology, such as into nanowires, nanotubes, nanoparticles (NPs), or porous frameworks[61]. Modifying these structures enables faster and more concentrated interactions between the sensing material and target gases, thereby markedly enhancing sensor sensitivity. In general, materials with larger surface areas exhibit higher response levels due to the increased number of active sites available for gas-solid interactions. Moreover, porous structures with interconnected channels facilitate gas diffusion within the sensing layer, improving contact between the target gas and the material, thereby enhancing reaction efficiency[62,63]. Consequently, nanostructured and porous materials are widely employed to increase surface area and improve sensor performance.

Grain size

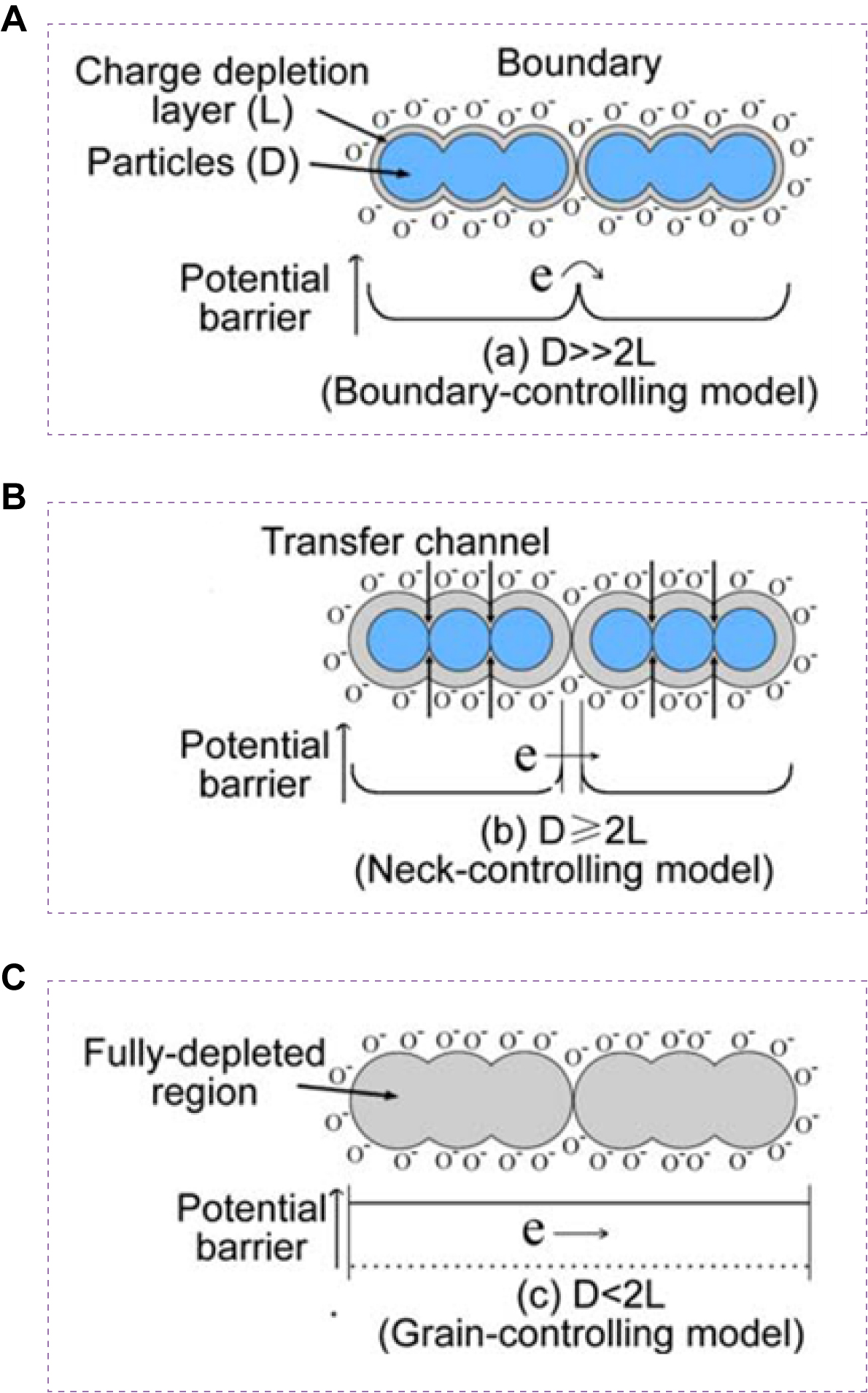

Grain size is a critical factor influencing variation in resistance and overall gas sensing performance. Numerous studies have demonstrated its impact on the sensing behavior of metal oxides[64-67]. As shown in Figure 3, sensing materials consist of partially sintered grains connected by necks, which further assemble into larger aggregates through grain boundaries. At the grain surface, adsorbed oxygen molecules withdraw electrons from the conduction band and trap them in ionic form, inducing band bending and generating electron-depleted space-charge layers. When the grain size becomes comparable to or smaller than twice the thickness of the space-charge layer, sensor sensitivity increases markedly[68]. Xu et al. explained this behavior using a semi-quantitative model[69]. Depending on the relationship between grain size (D) and the width (L) of the space-charge layer induced by chemisorbed ions, three regimes can be distinguished. (i) D >> (indicates far exceeding) 2L. Conductivity is dominated by internal charge carriers and follows an exponential dependence on barrier height. In this case, the effect of charges generated by surface reactions is relatively minor; (ii) D ≥ 2L. Space-charge layers at grain necks form constricted conduction channels within aggregates. Conductivity is determined by both interparticle barriers and the channel cross-sectional area, making it highly sensitive to variations in surface charge; (iii) D < 2L. The space-charge layer extends throughout the entire grain, depleting most mobile carriers. Conductivity is then governed primarily by intergranular transport, and even small amounts of surface charge can induce large changes in overall conductivity. Therefore, when the grain size approaches the critical dimension, the material exhibits exceptionally high sensitivity to ambient gas molecules.

Figure 3. Schematic illustration of the effect of grain size on MOS sensor sensitivity. (A) D >> 2L; (B) D ≥ 2L; (C) D < 2L. This figure is quoted with permission from Sun et al.[68]. MOS: Metal oxide semiconductor.

STRATEGIES TO ENHANCE SENSING PERFORMANCE

In the field of gas sensing, MOS materials have been widely employed owing to their excellent sensing properties. With ongoing technological progress and increasing environmental demands, the performance requirements for gas sensors have become more stringent. Modern gas sensors are expected to deliver high sensitivity, excellent selectivity, fast response and recovery, long-term stability, and low power consumption. However, single-component MOS materials used in resistive sensors often fail to meet all these criteria simultaneously. To overcome this limitation, extensive efforts have been devoted to improving their sensing performance, leading to the development of several effective strategies. These include the construction of mesoporous metal oxides[70,71], elemental doping[72,73], noble metal loading[21,74], and heterojunction engineering[75-77], which will be discussed in the following sections.

Constructing mesoporous metal oxides

Among various nanomaterials, mesoporous metal oxides constitute a distinctive class of functional porous materials with tunable pore sizes ranging from 2 to 50 nm. Owing to their adjustable pore structures and compositions, large specific surface areas and pore volumes, unique electronic structures, and facile surface modification, they have attracted significant attention in gas sensing[15,78]. The high surface area and highly crystalline frameworks offer abundant active sites and reaction interfaces, promoting gas adsorption and surface reactions, and thereby enhancing sensor sensitivity. Meanwhile, well-interconnected mesoporous channels improve gas diffusion and mass transfer, increasing the likelihood of gas-solid interfacial interactions. This accelerates adsorption and catalytic reactions, further boosting sensitivity and lowering detection limits. In addition, their highly crystalline frameworks facilitate charge-carrier transport and the detection of carrier-density changes, leading to faster response and recovery. These characteristics make mesoporous metal oxides promising candidates for advanced semiconductor gas sensors with high sensitivity, low detection limit, and rapid response-recovery rate. Consequently, the construction of mesoporous metal oxides is an effective strategy for enhancing gas sensing performance.

Various synthetic strategies, including hard-template (nano-casting), soft-template, and self-templating methods, have been developed to control the morphology and dimensions of mesoporous metal oxides. By selecting appropriate preparation techniques, their mesostructures can be precisely tailored, thereby optimizing gas sensing performance.

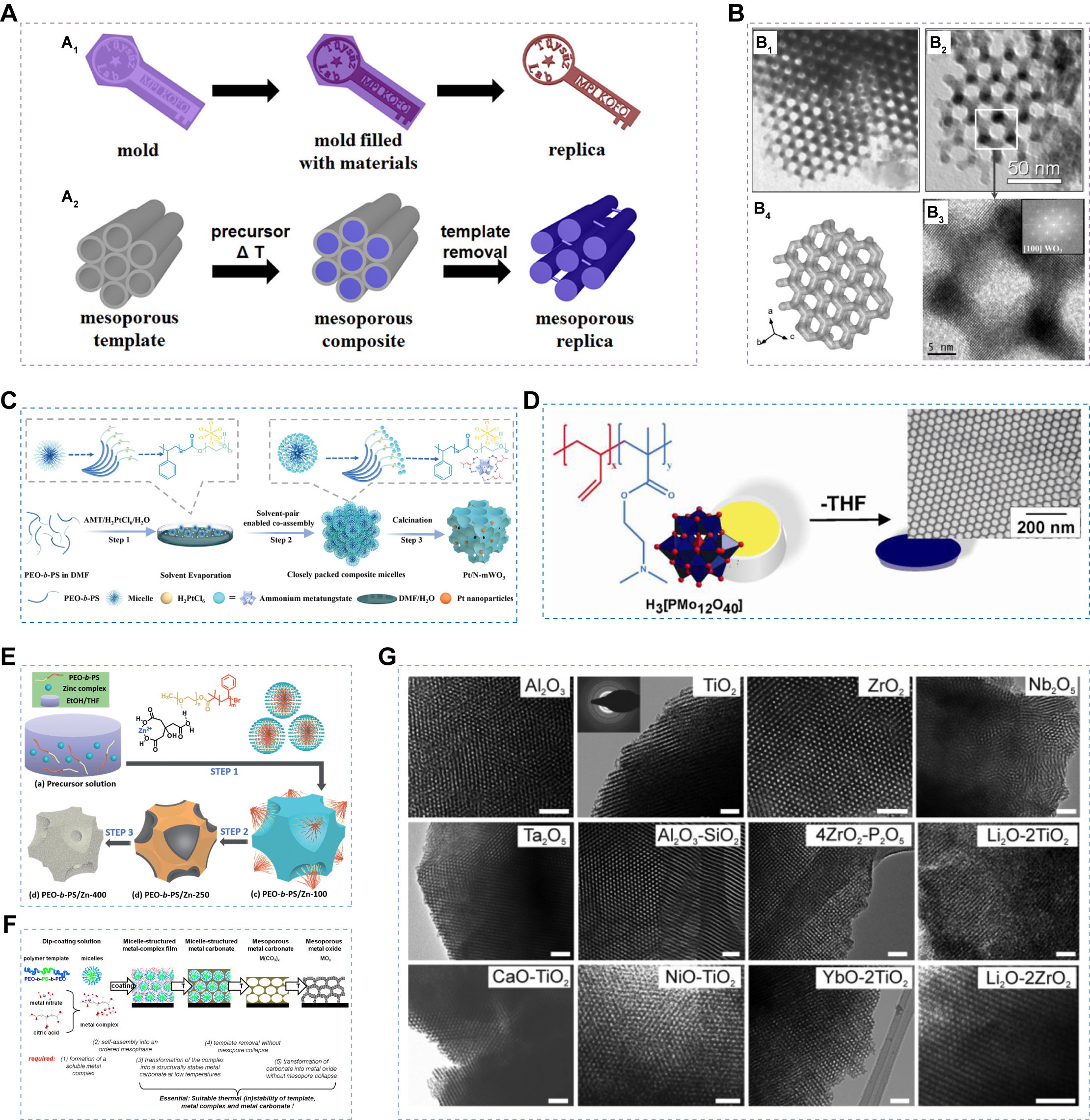

Hard-template method

The hard-template method, also known as nano-casting, typically employs pre-synthesized mesoporous materials such as mesoporous silica or carbon as sacrificial scaffolds. The inorganic precursor is impregnated into the template channels to fill the mesopores, followed by thermal treatment to convert it into the corresponding crystalline metal oxide. Subsequent removal of the template yields the desired mesoporous metal oxide framework [Figure 4A][70]. This method offers several advantages. First, it avoids the use of structure-directing agents and bypasses the complex hydrolysis-condensation of inorganic precursors, making it highly versatile for synthesizing various mesoporous materials. Second, mesoporous silica and carbon templates are chemically and thermally stable, and their well-defined channels can be readily infiltrated by appropriate precursors. As a result, the hard-template strategy has been successfully applied to fabricate diverse mesoporous materials, including metal oxides[79], metal sulfides[80], metal nitrides[81], and metal carbides[82]. For example, ordered mesoporous WO3 (mWO3) structures have been obtained using KIT-6 as a template [Figure 4B][79]. Moreover, Deng et al.[70] synthesized a series of ordered mesoporous transition metal oxides, such as Co3O4, NiO, Fe2O3, Cr2O3, and Mn3O4, by employing ordered mesoporous silicas [ Mobil Composition Of Matter N. 41 (MCM-41), Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology-6 (KIT-6), and Santa Barbara Amorphous-15 (SBA-15)] as hard templates.

Figure 4. (A) Schematic illustration for the casting process of a key with a mold (A1) and nanocasting using ordered mesoporous materials as the hard template (A2). Figure 4A is quoted with permission from Deng et al.[70]; (B) TEM images of mesoporous WO3 synthesized using KIT-6 as the template (B1, B2); HRTEM image of the ring-like structure, with the inset showing the corresponding FFT pattern (B3); uncoupled framework model (B4). Figure 4B is quoted with permission from Rossinyol et al.[79]; (C) Schematic illustration of the EIAA strategy. Figure 4C is quoted with permission from Jianget al.[24]; (D) Schematic illustration of the one-pot direct synthesis of PB-b-PDMAEMA/H3[PMo12O40] nanocomposite films. Figure 4D is quoted with permission from Lunkenbein et al.[85]; (E) Schematic illustration of the citrate ligand-assisted EISA method for synthesizing crystalline mZnO. Figure 4E is quoted with permission from Zhou et al.[25]; (F) Schematic illustration of the synthesis routes for mesoporous metal oxides via metal carbonate intermediates. Figure 4F is quoted with permission from Eckhardt et al.[86]; (G) TEM images of multicomponent mesoporous metal oxides prepared with acetate chelation assistance. Figure 4G is quoted with permission from Fan et al.[87]. THF: Tetrahydrofuran; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; HRTEM: high-resolution transmission electron microscopy; FFT: fast Fourier transform; EIAA: evaporation-induced aggregate assembly; PDMAEMA: poly(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate); H3[PMo12O40]: phosphomolybdic acid; mZnO: mesoporous zinc oxide.

However, the rigid structural constraints of templates such as mesoporous silica and carbon make it difficult to flexibly tune the pore characteristics of the resulting materials, including their dimensions, types, window sizes, and connectivity. In particular, template removal typically requires hazardous chemicals such as hydrofluoric acid or hot potassium or sodium hydroxide solutions, which pose environmental risks and health hazards to operators. Therefore, the hard-template method is associated with high costs, complex procedures, and poor environmental compatibility, limiting its suitability for large-scale production.

Soft-template method

The soft-template method is considered one of the most effective and versatile strategies for fabricating ordered mesoporous materials through controlled co-assembly. Classical soft-templating is primarily realized via evaporation-induced self-assembly (EISA) or evaporation-induced aggregate assembly (EIAA) strategies [Figure 4C][24]. In these processes, weak interactions between inorganic precursors and organic surfactants (e.g., block copolymers) are crucial. These interactions cooperatively drive complex hydrolysis-condensation through multiple forces, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and covalent bonding, leading to the formation of uniform organic-inorganic micelles. As solvents such as tetrahydrofuran, acetone, or methanol evaporate, the mixed micelles pack densely to generate ordered mesoporous frameworks. Despite its advantages, synthesizing ordered mesoporous metal oxides remains challenging due to the intrinsically weak inorganic-surfactant interactions, the limited control over hydrolysis-condensation, and the structural instability of porous networks during high-temperature treatment[83]. To overcome these limitations, numerous strategies have been developed to strengthen inorganic-organic interactions and regulate precursor hydrolysis-condensation behaviors.

Specifically, the interactions between inorganic species and surfactants can be strengthened by selecting appropriate precursors and organic polymer templates. For example, Zhang et al. employed a laboratory-synthesized amphiphilic block copolymer, polystyrene-b-poly(4-vinylpyridine) (PS-b-P4VP), as the structure-directing agent and tetrabutyl titanate (TBOT) as the titanium source to prepare nitrogen (N)-doped ordered mesoporous TiO2[84]. Strong chelation between the pyridine nitrogen and titanium enabled the formation of an ordered mesoporous TiO2 framework with high crystallinity, without the need for additional additives during synthesis. Similarly, Lunkenbein et al. used the diblock copolymer poly(butadiene-block-2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate) (PB-b-PDMAEMA) and phosphomolybdic acid (H3[PMo12O40]) to fabricate mesoporous films, leveraging strong electrostatic interactions between protonated poly(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate) (PDMAEMA) segments and PMo12O403- anions [Figure 4D][85].

Small-molecule ligands can act as “bridges” that strengthen coordination between inorganic species and surfactants, thereby promoting organic-inorganic co-assembly. For example, Zhou et al. used citric acid to assist the formation of mesoporous ZnO by enhancing the interaction between Zn2+ ions and poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) segments [Figure 4E][25]. Citric acid induces partial hydrolysis of zinc nitrate to form zinc citrate, which then binds to ethylene oxide segments through hydrogen bonding. Similarly, Eckhardt et al. employed citric acid as a chelating agent to form stable metal-citrate complexes, which subsequently interact with block copolymers to generate ordered mesophases, yielding ZnO and Co3O4 films with ordered mesopores [Figure 4F][86]. Fan et al. further showed that controlled coordination of metal ions with acetic acid produces nanoscale particles with uniform condensation kinetics, where acetate ligands bridge amphiphilic copolymers and inorganic species[87]. Replacing hydrolysable alkoxy groups with acetate lowers the cross-linking density within the gel network, enabling the synthesis of multicomponent mesoporous oxides [Figure 4G]. Overall, tailored ligands serve as effective molecular linkers, guiding the formation of well-organized mesostructures.

The rapid hydrolysis-condensation of inorganic precursors, such as metal chlorides and alkoxides, often induces phase separation and agglomeration, resulting in disordered structures. To overcome these issues, various modifiers, including hydrochloric acid, nitric acid, and acetylacetone, have been introduced to regulate hydrolysis kinetics. For example, Li et al. used hydrochloric acid as a modifier and poly(ethylene oxide)-b-polystyrene (PEO-b-PS) as a template to fabricate ordered mWO3 with a highly crystalline framework[47]. HCl suppresses the hydrolysis of WCl6 while protonating PEO segments, thereby strengthening hydrogen bonding between hydrophilic tungsten species and the template. Similarly, Wei et al. synthesized mesoporous Al2O3 using aluminum acetylacetonate as the precursor and nitric acid as a modifier[88]. Nitric acid slows hydrolysis, whereas acetylacetonate ligands form chelated complexes that further stabilize Al species. Chelating agents also inhibit aggregation during hydrolysis. Xiao et al. employed acetylacetone to retard SnCl4 hydrolysis, forming acetylacetonate-stabilized tin hydroxide nanoclusters (NCs) with controllable sizes suitable for subsequent co-assembly with block copolymers[89]. An alternative strategy involves the direct co-assembly of preformed nanocrystals with amphiphilic block copolymers, thereby bypassing complications associated with precursor hydrolysis[78]. Corma et al. demonstrated this approach by co-assembling monodisperse CeO2 NPs with PEO20-PPO70-PEO20 (P123) to produce mesostructures exhibiting excellent ordered hexagonal symmetry and exceptional thermal stability up to 700 °C[90]. This strategy has been extended to other oxides such as In2O3[91], TiO2[91], ZnO[92], CuO[92], Mn3O4[93], ZrO2[94], and hybrid oxides including ITO[91] and MnFe2O4[93].

Commercial Pluronic surfactants composed of non-ionic PEO and poly(propylene oxide) (PPO), such as P123[90] and PEO102-PPO65-PEO102 (F127)[95], have been widely used in the synthesis of mesoporous materials. However, their low thermal stability makes it difficult to obtain highly crystalline frameworks. High-temperature annealing often leads to partially crystalline porous structures or even the collapse of metal oxide frameworks. To address this limitation, amphiphilic block copolymers with higher thermal stability and molecular weight, such as PEO-b-PS[47], PS-b-P4VP[84], polystyrene-block-poly(2-vinylpyridine) (PS-b-P2VP)[96], and poly(isoprene)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) (PI-b-PEO)[97], have been employed to prepare mesoporous metal oxides with large pore diameters and high crystallinity. Lee et al. first reported a combined soft-hard template co-assembly (CASH) method using PI-b-PEO as the structure-directing agent[97]. In this process, samples were initially calcined under an inert atmosphere. The PEO segments decomposed readily upon heating, whereas the thermally stable polyisoprene (PI) segments [each containing two s orbital and two p orbitals hybridized (sp2)-hybridized carbons] carbonized to form rigid amorphous carbon, which acted as a scaffold to support the intermediate oxide walls. Subsequent calcination in air removed the residual carbon, yielding highly crystalline mesoporous metal oxides. More recently, our group has further advanced the CASH method by employing PEO-b-PS as templates. A series of mesoporous metal oxides, including WO3[47], TiO2[98], SnO2[89], ZnO[92], CuO[92], and Al2O3[88], have been successfully synthesized through gas-liquid interfacial assembly.

Furthermore, incorporating soluble phenolic formaldehyde resin (resol) and silicate species into the framework has been shown to effectively prevent structural collapse during high-temperature processing. Inspired by this concept, Li et al. developed a pore-engineering strategy using hydrophilic resol as a sacrificial carbon source to synthesize ordered mWO3 with well-connected bimodal pores and crystalline pore walls[99]. In this system, resol preferentially interacts with PEO segments and acts as a binder that links tungsten species with the PEO-b-PS template. During thermal treatment, both the carbonized resol and the copolymer form a rigid matrix that stabilizes the pore structure, yielding highly crystalline hierarchical mWO3. Zhou et al. reported the controlled synthesis of silica-filled mesoporous ZnO[100]. Citric acid was employed as a chelating agent to strengthen the weak interactions between the zinc precursor and the PEO-b-PS template. Simultaneously, tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS)-derived silicate oligomers interacted with citric acid through hydrogen bonding, enabling co-assembly with the zinc precursor and providing additional structural support during high-temperature processing.

These sophisticated assembly strategies, including ligand-assisted soft-templating, substitution of inorganic salts with preformed nanocrystals or NCs, sp2 carbon support, and amorphous component (phenolic resin or silicate)-assisted assembly, enable more controllable construction of mesoporous MOS materials with tunable pore architectures and precisely engineered surface properties, paving the way for high-performance gas sensor fabrication.

Self-template method

MOFs represent a distinctive class of porous organic-inorganic hybrid materials constructed through the coordination assembly of metal ions or clusters with organic ligands. Owing to their tunable porosity, high surface areas, compositional diversity, and relatively straightforward synthesis, MOFs have attracted considerable attention in recent years. Representative families include the zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs)[101], the Materials of the Lavoisier Institute (MIL) series[102], and the University of Oslo (UIO) series[103]. These materials have been widely applied in gas separation, sensing, catalysis, and energy storage and conversion[104]. Upon high-temperature calcination in air, the metal centers within MOFs are converted into crystalline metal oxides. At the same time, the organic ligands decompose into gaseous products such as CO2 and NO2, thereby forming mesoporous structures. Since this self-templating pyrolysis strategy requires no additional templating agents, it has emerged as an attractive alternative route for synthesizing mesoporous MOS materials.

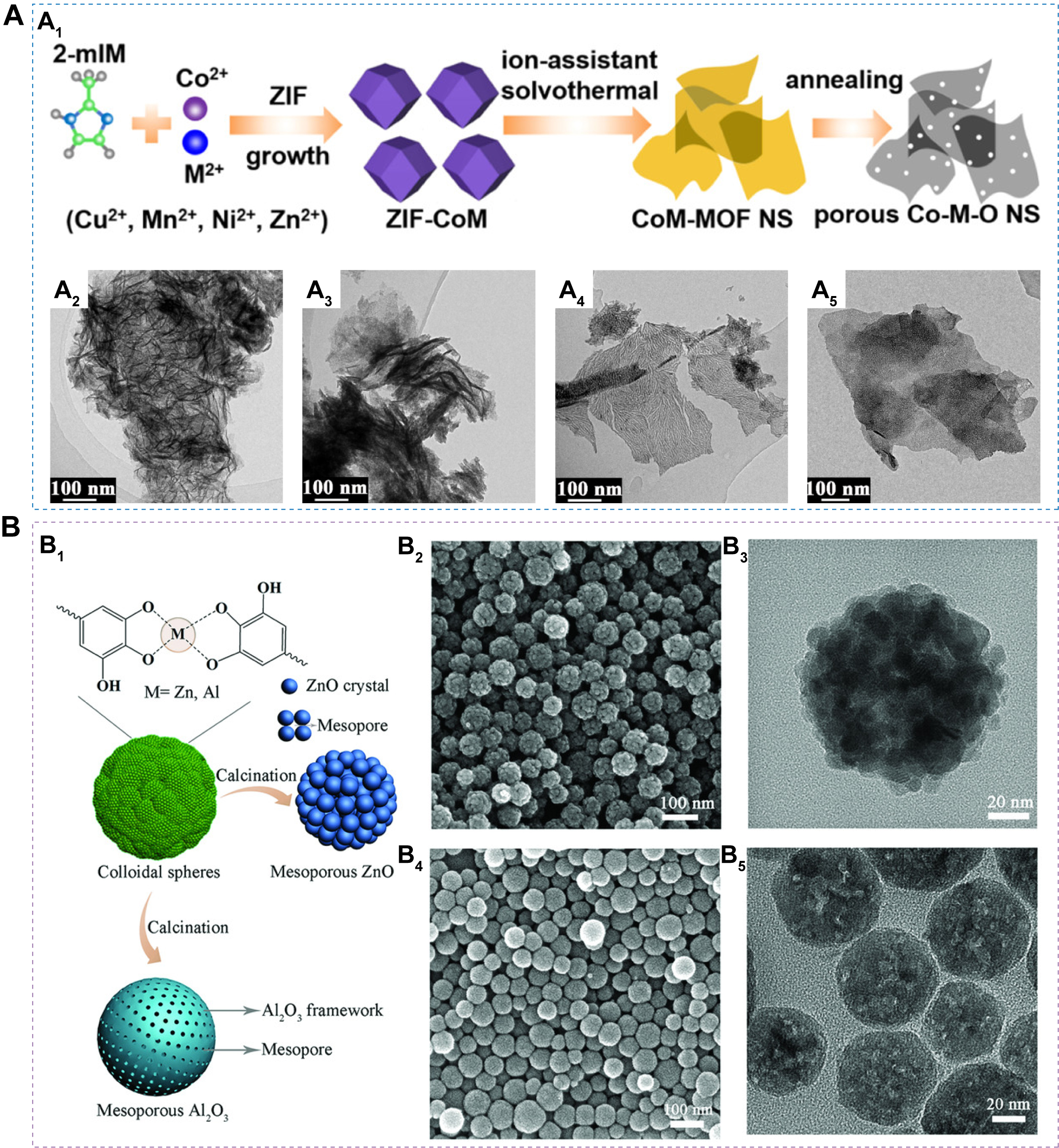

Mesoporous MOS derived from MOFs largely retain the structural features of their parent frameworks, and a variety of mesoporous MOS sensing materials with tunable morphologies have been obtained by precisely regulating MOF precursors. Wang et al. synthesized copper-based MOF [Hong Kong University of Science and Technology-1 (HKUST-1)] crystals with distinct polyhedral shapes by adjusting the amount of lauric acid as a growth modulator, and subsequent thermal treatment produced Cu2O/CuO sensing materials with octahedral, truncated octahedral, and cubic morphologies[105]. Among these, the octahedral structure with the largest specific surface area exhibited the best ethanol sensing performance. Jang et al. constructed a chrysanthemum-like layered ZnO/Co3O4 composite by in situ coupling rod-like ZIF-67 with sheet-like ZIF-8, followed by calcination[106]. This hierarchical structure, featuring abundant p-n heterointerfaces and high porosity, significantly enhanced acetone sensing, achieving an Ra/Rg of 29.0 to 5 ppm acetone, far exceeding that of pure Co3O4 rods (Ra/Rg = 1.05 at 5 ppm acetone). Li et al. further utilized MOFs as self-templates to synthesize uniform hollow La2O3/In2O3 nanotubes, which exhibited excellent triethylamine (TEA) sensing performance with a high Ra/Rg value of 458.13 to 50 ppm at 120 °C[107]. Such excellent performance can be attributed to the synergistic modulation of the electronic structure and the abundance of acidic sites. Using bimetallic MOFs as precursors, Qin et al.[108] prepared a series of ternary Co-M-O NSs (M = Cu, Mn, Ni, Zn) with ultrahigh surface areas and homogeneous compositions [Figure 5A], which displayed excellent CO sensing performance, including fast response-recovery rates, high stability, and good selectivity. Koo et al. developed PdO-ZnO/ZnCo2O4 HSs by depositing CoZn bimetallic ZIF onto polystyrene spheres, encapsulating Pd NPs within the cavities, and subsequently performing calcination[109]. The resulting p-ZnCo2O4/n-ZnO heterostructure facilitated electron sensitization, thereby endowing the HSs with outstanding acetone-sensing performance. When ternary phases fail to form or stoichiometry is suboptimal, bimetallic oxide composites can still be obtained, as exemplified by In2O3/ZnO porous hollow nanocages derived from InZn-MOF[110], NiO/CuO hydrangea-like composites from NiCu-BTC[111], and NiO/NiCo2O4 multilayer HSs from NiCo-BTC[112]. Moreover, noble metal NPs can be uniformly incorporated into oxide matrices by calcining catalyst-encapsulated MOFs (M@MOFs). For example, Koo et al. used ZIF-8 to support Pd NPs (Pd@ZIF-8), which were subsequently embedded into electrospun fibers and thermally treated to yield Pd@ZnO-WO3 nanofibers (NFs) with excellent toluene sensing properties[113]. In a follow-up study, the same group synthesized PdO-Co3O4 hollow nanocages by calcining Pd@ZIF-67[114], which showed high acetone responses due to the uniform dispersion of PdO catalysts and improved gas accessibility within the hollow structures.

Figure 5. (A) Schematic illustration of ternary metal oxide nanosheet synthesis (A1), and TEM images of Co-Cu-O (A2), Co-Mn-O (A3), Co-Ni-O (A4), and Co-Zn-O (A5). Figure B is quoted with permission from Qin et al.[108]; (B) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of ZnO and Al2O3 (B1); SEM image (B2) and TEM image (B3) for Zn-tannic acid coordination polymer; SEM image (B4) and TEM image (B5) for Al-tannic acid coordination polymer. Figure 5B is quoted with permission from Wang et al.[116]. ZIF: Zeolitic imidazolate framework; MOF: metal-organic framework; NS: nanosheet; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscope.

In addition to MOFs, plant-derived polyphenols, as a naturally abundant, nontoxic, and environmentally friendly biomass, have recently emerged as powerful precursors for constructing functional mesoporous nanomaterials[115]. Owing to their strong chelating ability toward metal ions, plant polyphenols readily coordinate with various metal species through metal-catechol complexation, forming stable metal-phenolic coordination polymer networks. Upon subsequent calcination, the polyphenol scaffold decomposes into CO2 and H2O, while the coordinated metal centers undergo oxidation and crystallization, producing mesoporous metal oxides. Because the limited amount of metal species cannot fully inherit the morphology of the parent metal-phenolic framework, extensive mesopores and internal cavities are generated during pyrolysis.

Wang et al. developed a general metal-polyphenol self-templating strategy for synthesizing mesoporous metal oxide microspheres with diverse compositions (Al2O3, ZnO, Fe2O3, Co3O4, and CuO) and highly crystalline frameworks [Figure 5B][116]. Owing to the universal chelation capability of polyphenols toward a wide range of metal ions, this method enables the synthesis of binary, ternary, and even high-entropy mesoporous metal oxides. Using tannic acid as a universal ligand, Wang et al. further demonstrated the fabrication of binary (Fe-Co, Ni-Co, Ni-Zn oxides), ternary (Ni-Co-Zn and Ni-Co-Mn oxides), and quinary (Ni-Co-Fe-Cu-Zn oxides) mesoporous nanospheres[117]. Depending on the intrinsic crystallization temperature and thermal evolution of different metal species, various architectures, such as solid[118], hollow[117], and multi-shell[119] mesoporous structures, can be obtained. These features arise from the nonuniform shrinkage and structural reorganization of metal-phenolic precursors during calcination. Moreover, plant polyphenols exhibit rich structural diversity and tunable chemical functionality. By employing different polyphenols as organic ligands, the morphology of metal-phenolic coordination networks can be flexibly tailored into nanospheres, NFs, NSs, and polyhedra, which are subsequently inherited by the derived mesoporous metal oxides.

Mesoporous semiconductor oxides derived from metal-phenolic self-templating possess high surface area, abundant porosity, compositional tunability, and diverse morphologies, making them highly promising for gas sensing applications[120]. For instance, Feng et al. used polyphenols as molecular glues to co-assemble glutathione-protected Au NCs with Sn species, forming hybrid metal-phenolic nanospheres[121]. After calcination, the Au NCs were unexpectedly converted into atomically dispersed Au single atoms embedded in the mesoporous SnO2 framework. The resulting sensor exhibited an exceptionally high response (587.3) to 2 ppm 3-hydroxy-2-butanone (3H-2B) at 50 °C, an enhancement of 183.5-fold compared with pristine mesoporous SnO2. Additionally, the optimal operating temperature was effectively reduced from 100 °C to 50 °C. Similarly, Li et al. employed the same self-templating process to synthesize Au/Pd dual-atom-sensitized mesoporous SnO2 for H2 detection, achieving an ultralow detection limit (70 ppb), fast response (100 s), and strong resistance to CO, NO, H2S, and SO2 interference[122]. Importantly, polyphenols serve as versatile molecular glues that interact with diverse substrates through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic forces, π-π stacking, and covalent coupling[123]. After thermal treatment, mesoporous metal oxide films can be deposited directly onto different substrates, offering opportunities for in situ solution-grown, structurally stable multicomponent MOS devices. Furthermore, as naturally abundant biomass molecules, polyphenols can be produced on a large scale, providing a promising foundation for scalable manufacturing of mesoporous metal oxide materials.

Thus, the self-templating strategy has opened new avenues for the rational design of mesoporous MOS materials. By tailoring MOF and metal-phenolic precursor structures and carefully controlling synthesis parameters, the size, morphology, composition, and electrical conductivity of mesoporous MOS can be precisely tuned. Materials synthesized through this approach exhibit unique physicochemical properties and hold great promise for high-performance gas sensing applications.

Overall, the construction of mesoporous architectures remains a fundamental and highly effective strategy for enhancing the gas sensing performance of MOS. Hard-template, soft-template, and self-templating approaches each offer distinctive advantages [Table 1]. The hard-template method enables precise structural replication and well-defined pore ordering, but typically involves multistep procedures and environmentally hazardous template-removal processes. The soft-template approach provides greater versatility and tunability, allowing fine control over pore size and channel configuration. However, it requires meticulous regulation of intermolecular interactions and often faces challenges in maintaining structural integrity during high-temperature calcination. Self-templating routes, including MOF- and metal-polyphenol-derived strategies, feature simplified synthesis and rich compositional adaptability, although the final morphology inherently depends on the structure and chemistry of the precursor framework. In practical applications, the choice among these methods must balance the target pore architecture, desired crystallinity, processing complexity, and cost considerations.

Comparison of mesoporous construction methods

| Strategy | Template type | Pore ordering | Framework crystallinity | Cost & scalability | Advantages | Limitations | Performance enhancement effect |

| Soft-template | Surfactants, block co-polymers | High ordering | Medium | Low cost, scalable | Flexible, universal, tunable | Low thermal stability | Constructing large specific surface areas and interpenetrating pore channels, increasing gas adsorption sites and catalytic active sites |

| Hard-template | Ordered mesoporous silica/carbon | High ordering | High | Higher cost, multi-step procedure | Precise pore control | Harsh template removal procedure | Providing high specific surface areas and uniform diffusion channels, facilitating enhanced sensitivity and response speed |

| Self-template | Metal-organic frameworks | Low ordering | High | Depending on the precursor type | Available for diverse components and morphologies | Strong template dependency | Inheriting the porosity of precursor templates, providing large specific surface areas and abundant active sites, with synergistic component effects |

Elemental doping

Elemental doping, which introduces foreign elements into host materials, has been shown to markedly enhance the sensing performance of MOS. Doping not only tailors the electronic structure but also affects structural characteristics such as grain size and morphology, thereby modulating the overall sensing behavior. Rare-earth elements, transition metals, and non-metal elements can all act as effective dopants. Through judicious selection and design, dopants enable precise control over the electronic and structural properties of MOS, allowing their sensing performance to be optimized for diverse application scenarios.

Rare-earth element doping

Rare-earth elements (REs, including La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, and Yb) possess a unique 4f-electron configuration. Owing to their exceptional electrical conductivity, luminescence, and catalytic properties, they have been widely employed as effective dopants in catalysis and sensing applications[124-126]. Rare-earth oxides typically exhibit high oxygen-ion mobility, favorable catalytic activity, and strong surface alkalinity, which enhance gas sensing performance, particularly in terms of response and selectivity. In addition, rare-earth doping can reduce grain size and increase oxygen vacancy (Ov) concentrations, thereby further improving the sensing characteristics of MOS. Extensive studies have demonstrated that rare-earth elements play a pivotal role in optimizing the gas sensing properties of MOS.

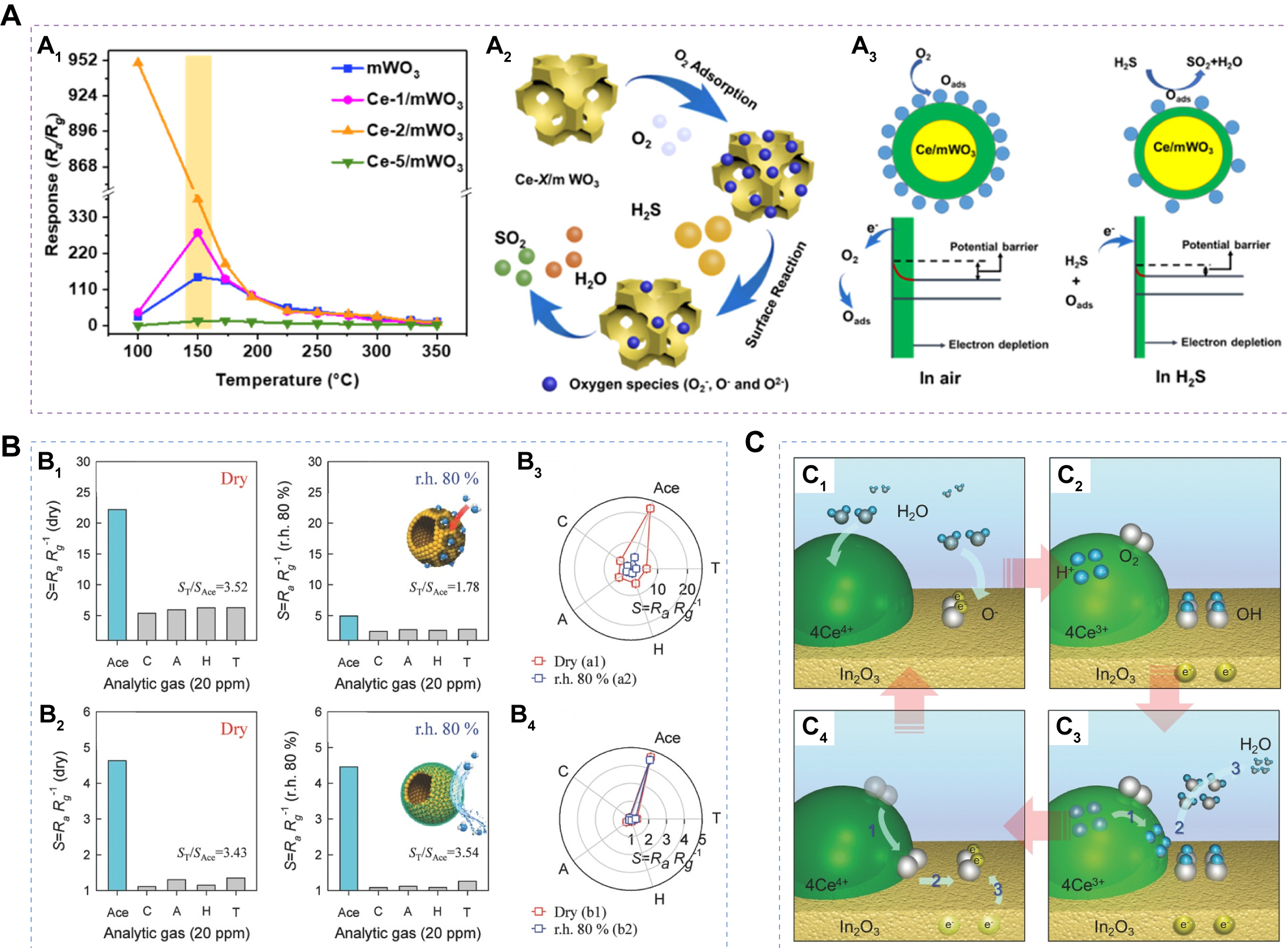

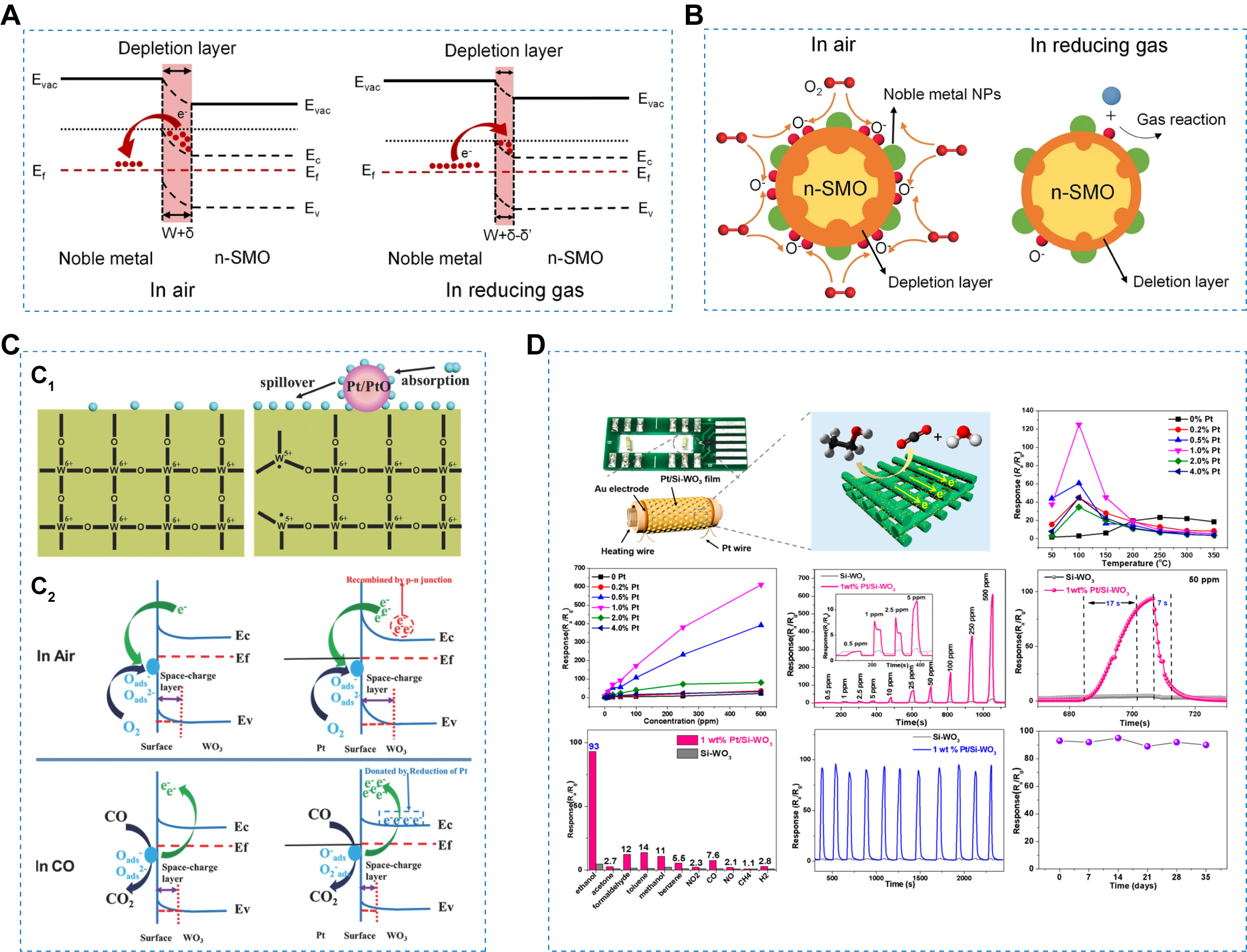

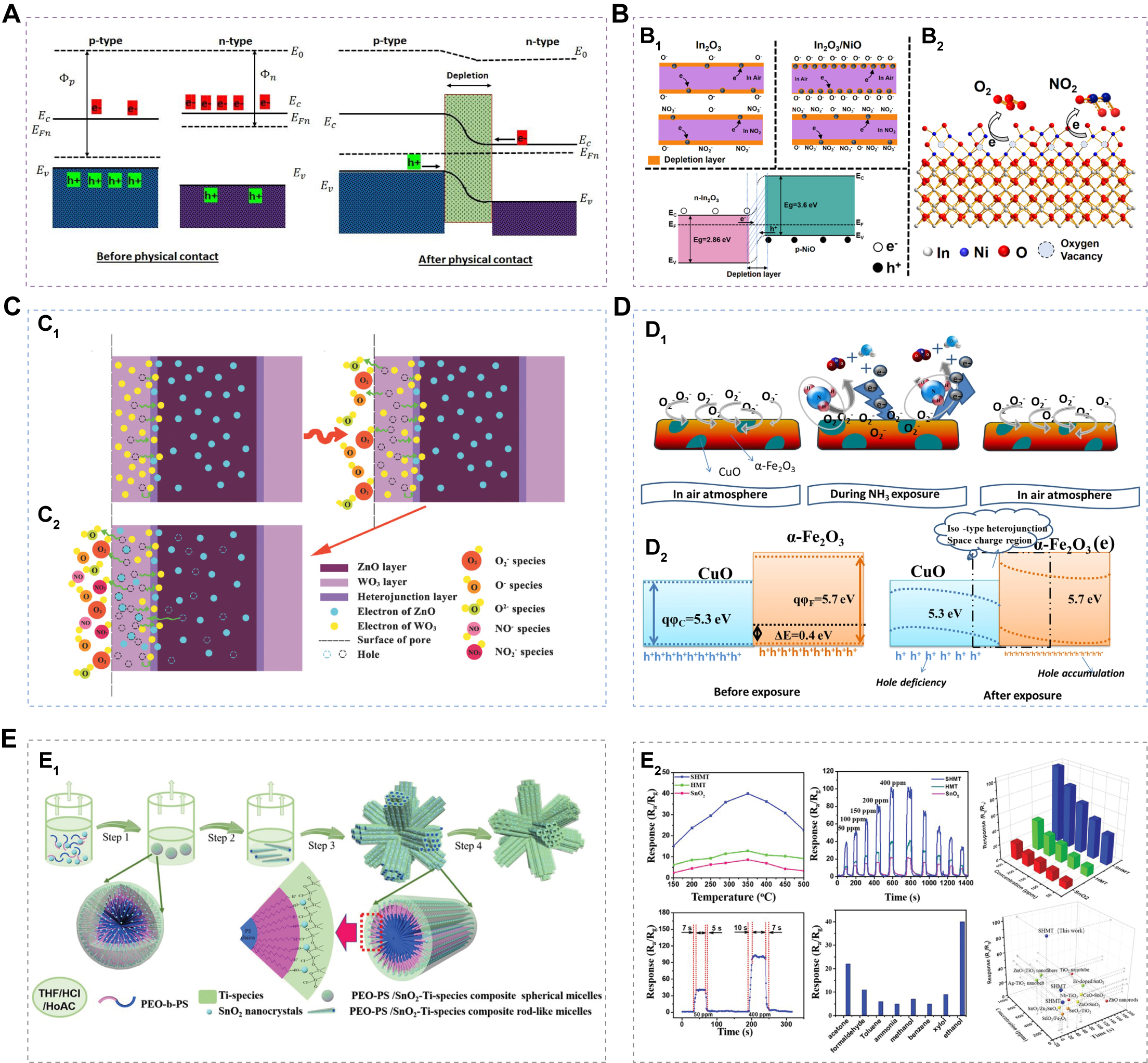

Liu et al. synthesized Ce-doped ordered mWO3 via a straightforward in situ co-assembly approach. Ce doping effect can modulate the coordination environment of W atoms, significantly enhancing Ov and forming Wδ+-Ov sites[127]. Therefore, the resulting Ce-doped WO3 exhibits outstanding H2S sensing performance at low operating temperatures (150 °C), with a high response value of 381 (for 50 ppm), rapid response dynamics (6 s), excellent selectivity, moisture resistance, and good long-term stability [Figure 6A]. Zhao et al. employed an electrospinning strategy to synthesize a series of one-dimensional In2O3 NFs doped with various rare-earth elements (RE-In2O3, RE = Y, La, Nd, Ho, and Tm)[128]. All RE-In2O3 materials exhibited enhanced formaldehyde responses compared to pristine In2O3. Among these, Y-In2O3 demonstrated the highest responsivity and excellent selectivity, which was attributed to the elevated Fermi level and increased surface alkalinity of In2O3, resulting in enhanced oxygen chemisorption and formaldehyde adsorption. Bai et al. prepared pristine In2O3 and RE (Ce, Tm, Eu, Er, and Tb)-doped In2O3 nanotubes via electrospinning. Rare-earth doping markedly improved ethanol sensing, although the extent of enhancement varied among different dopants. Mechanistic analyses indicated that doping modifies the types and distribution of adsorbed oxygen species on the material surface, thereby boosting gas sensing activity[129]. Wang et al. synthesized pristine SnO2 and Tb-doped SnO2 nanotubes with different doping concentrations using uniaxial electrospinning[130]. Tb doping induced pronounced morphological changes, including increased surface roughness, reduced nanotube diameter, and smaller SnO2 grain size. Notably, the 7 mol% Tb-SnO2 nanotubes exhibited the highest response to ethanol, which was attributed to the synergistic effects of reduced grain size, defect generation, structural disorder, enhanced surface alkalinity, and increased roughness introduced by doping. Li et al. fabricated pure MoO3 and Ce-doped MoO3 nanoribbons via a one-step hydrothermal method[131]. Ce doping not only increased the response toward trimethylamine (TMA) but also reduced the optimal operating temperature. The authors proposed that substitution of Mo sites by Ce atoms promotes Ov formation, which facilitates oxygen adsorption and improves sensing performance. Furthermore, Lee et al. have reported several humidity-insensitive sensing materials, including CeO2-loaded In2O3 HSs[132], Tb-doped SnO2 yolk-shell microspheres[133], and Pr-doped In2O3 macroporous microspheres[134]. They attributed this humidity resistance behavior to the +3/+4 redox transitions of multivalent rare-earth elements (Ce, Pr, Tb), which promote the removal of surface hydroxyl groups, the regenerative adsorption of oxygen, and electron consumption [Figure 6B and C]. These processes enhance sensor stability and gas sensing performance by establishing a water-poisoning-resistant reaction pathway.

Figure 6. (A) Sensing responses of the Ce-X/mWO3 sensor to 50 ppm H2S at various temperatures (A1); Sensing mechanism of Ce-X/mWO3-based gas sensors for H2S detection (A2). Energy band structure and electron-transfer process of Ce-X/mWO3 sensitive material exposure in air and H2S-air mixture (A3). Figure 6A is quoted with permission from Liu et al.[127];( B) Gas responses of pure In2O3 (B1) and 11.7 Ce-In2O3 (B2) hollow spheres exposed to 20 ppm acetone (Ace), CO (C), ammonia (A), H2 (H), and toluene (T) at 450 °C in dry and humidity (r.h. 80%); Polar plots of gas responses of pure In2O3 (B3)and 11.7 Ce-In2O3 (B4) hollow spheres exposed to various reducing gases in dry (red) and r.h. 80% (blue). C: Self-refreshing of the In2O3 sensing surface by the CeO2 nanoclusters. Water vapor inflow (C1), chemisorption (C2), desorption (C3), and oxygen ion regeneration (C4). Figure 6B and C is quoted with permission from Yoon et al.[132]. ppm: Parts-per-million.

Transition metal element doping

Transition metals constitute another important class of dopants for enhancing the gas sensing performance of MOS. Owing to their comparable atomic radii to those of common MOS hosts (e.g., W, In, Sn, Zn), many transition metals can be readily incorporated into the lattice through substitutional doping. Such doping not only modulates lattice parameters and oxygen adsorption but also alters defect and carrier concentrations, thereby regulating the overall sensing behavior. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of various transition metal-based dopants, including V[135], Cr[136,137], Mn[138], Fe[139], Co[140,141], Ni[142,143], Cu[144], and Mo[145,146].

Chen et al. synthesized Co-doped SnO2 sensing materials with a 3D anti-opalescent structure[141]. Among these, the Co-SnO2 sensor with a Co/Sn atomic ratio of 1:24 exhibited the best performance, showing ultrahigh sensitivity, fast response, and excellent selectivity toward low concentrations of formaldehyde (200 °C) and acetone (225 °C), respectively. Mechanistic investigations revealed that cobalt doping narrows the bandgap, elevates the Fermi level, and introduces vacancy defects through the reactions

where,

The electronic sensitization effect induced by transition metal doping can also occur in p-type MOS. Li et al. synthesized pure NiO and Cr-doped NiO NPs via a hydrothermal method and systematically investigated their gas sensing properties[137]. The 25 at% Cr-NiO sensor exhibited high sensitivity (Rg/Ra = 10.6 vs. 100 ppb), excellent selectivity, and good stability for benzyl mercaptan detection. As a p-type semiconductor, NiO conducts through holes. Substitutional Cr3+ doping at Ni2+ sites follows a charge compensation mechanism, as given below:

where

Simultaneously, oxygen molecules oxidize Ni2+ to Ni3+, generating abundant reactive O- species that amplify carrier concentration variations (Δp). Moreover, ionic species such as Ni2+ act as oxygen adsorption sites, forming reactive oxygen species that catalyze surface redox reactions, thereby further increasing Δp. From the perspective of electronic sensitization, the t2g orbitals of Ni overlap with p orbitals of oxygen, causing Pauli repulsion and facilitating partial electron transfer between metal centers and lattice oxygen. Due to the Oh symmetry of the octahedral MO6 unit, Ni2+ and Cr3+ have valence configurations of (t2g)6(eg)2 and (t2g)3(eg)0, respectively. Cr3+, with unfilled t2g orbitals, acts as an electron acceptor, whereas Ni2+, with a fully occupied (t2g)6 configuration, induces e--e- repulsion with the oxygen p orbitals, leading to electron transfer from Ni2+ to Cr3+. This process promotes the formation of Ni3+ species and enhances their electron affinity. The authors proposed that surface high-valence Ni plays a pivotal role in gas redox reactions, while doped Cr regulates carrier concentration and Cr-O-Ni charge transfer, synergistically improving gas sensing performance. Similar phenomena have been reported for Fe doping. Wang et al. synthesized a unique nest-like Fe-NiO structure, whose sensor exhibited a rapid response rate (26 s), short recovery time (5 s), and excellent selectivity toward TEA[139]. At 260 °C, its response to 50 ppm TEA reached 63, a 21-fold enhancement compared with pristine NiO. The improved performance was attributed to the distinctive nest-like architecture and the incorporation of Fe ions into the NiO nanocrystals.

Non-metal doping

The incorporation of non-metallic impurity atoms (e.g., C, N, Si, and S) into MOS frameworks has also been demonstrated to significantly enhance gas sensing performance. Compared with metallic dopants, non-metallic elements can induce the formation of amorphous species, improve thermal stability, enhance selectivity and sensitivity, and lower operating temperatures. Therefore, the rational design of non-metal doping strategies is of great importance for optimizing the performance of MOS sensing materials.

Carbon, an essential non-metal widely used in catalysis and energy conversion, can act as an effective dopant to modulate the micro/nanostructure and physicochemical properties of sensing materials, including localized electron distribution, surface active sites, and electrical conductivity. Raghu et al. synthesized C-doped TiO2 with abundant (101) crystal facets using urea as the carbon source via a mild pyrolysis process [Figure 7A][147]. The resulting material exhibited a markedly improved ethanol sensing response (34.8%) compared with pristine TiO2 (8.5%). Both substitutional and interstitial carbon doping generated abundant active sites, Ov, and chemisorbed oxygen species, which accelerated interfacial catalytic reactions. Moreover, graphitic carbon improved electrical conductivity and reduced the bandgap, thereby lowering the ethanol sensing operating temperature from 250 °C to 150 °C. Similarly, Zhao et al. developed a facile template-free solvothermal route to synthesize C-doped TiO2 NPs (~ 30 nm) without an additional carbon source[148]. The C-doped TiO2 exhibited outstanding alcohol sensing performance, with sensitivity increasing alongside carbon chain length. In particular, its response to n-pentanol was ~ 5.4 times higher than that of undoped TiO2. This improvement was attributed to enhanced conductivity, accelerated electron transfer, and increased surface-adsorbed oxygen, which collectively lowered the operating temperature and boosted sensitivity.

Figure 7. (A) Time-dependent ethanol gas sensing performances of TiO2 and C40-TiO2 sensor performances at 150 °C (A1); Ethanol gas sensing mechanism on pristine TiO2 and C40-TiO2. Figure 7A is quoted with permission from Raghu et al.[147]; (B) molecular structure of N-doped In2O3 (B1); SEM (B2) and TEM (B3) image of N-doped In2O3; The response transients of sensors to 10 ppm NO2 (B4); The linear fitting to the relationship between response and concentrations for In2O3 and N-doped In2O3 (B5). Figure 7B is quoted with permission from Mo et al.[150]; (C) Acetone sensing performance and mechanism of 3D cross-stacked Si-doped WO3 nanowire arrays. Figure 7C is quoted with permission from Ren et al.[153]; (D) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of the Ti3C2Tx MXene, sulfur-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene, and preparation of the MXene sensors (D1); Dynamic response curve of sulfur-doped Ti3C2Tx sensors for toluene at room temperature (D2). Figure 7D is quoted with permission from Shuvo et al.[156]. VOC: Volatile organic compound; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscope; ppm: parts-per-million.

Notably, carbon doping can also modify crystalline phases in WO3, thereby improving gas sensing performance. Wang et al. synthesized three-dimensionally ordered macroporous/mesoporous C-doped WO3 using polystyrene spheres as templates followed by post-heating[149]. Carbon atoms diffused into interstitial sites of the WO3 lattice, inducing the formation of ε-phase WO3. Benefiting from this unique crystal structure, the C-doped WO3 sensor exhibited high responsivity and selectivity toward acetone.

Beyond carbon doping, nitrogen incorporation into porous metal oxides can also markedly improve their gas sensing performance through distinct mechanisms. Mo et al. reported a novel N-doped indium oxide gas sensor, which shows a remarkable response to 10 ppm NO2 at room temperature, with outstanding long-term stability (over 30 days) and rapid response/recovery times (5/16 s) [Figure 7B][150]. Abbasi et al. employed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate the adsorption behavior of NO2 molecules on pristine and N-doped anatase TiO2 NPs[151]. Their results showed that NO2 adsorption on N-doped TiO2 is energetically more favorable than on pristine TiO2. Specifically, the nitrogen atom in NO2 preferentially binds to Ov and doped nitrogen sites on the TiO2 surface, while the oxygen atoms exhibit higher affinity for five-coordinated Ti atoms. Moreover, NO2 molecules are more easily oxidized to NO3- due to Ti-O bond cleavage between the TiO2 lattice and NO2. These factors collectively result in superior sensing performance of N-doped TiO2 compared with undoped NPs. Zhang et al. further reported a simple EIAA method for the in situ synthesis of N-doped ordered mesoporous TiO2[84]. The incorporation of nitrogen atoms into the TiO2 lattice led to smaller grain sizes and increased Ov concentrations, both of which enhance gas sensing activity. The resulting ordered mesoporous N-TiO2 sensor exhibited a response of 17.6 toward 250 ppm acetone, an 11.4-fold improvement compared with undoped TiO2. These improvements were mainly attributed to the open pore structure, large specific surface area, and abundant Ov. Additionally, nitrogen doping introduces impurity energy levels that lower the Fermi level of TiO2[152], thereby facilitating electron transfer from adsorbed target molecules to N-TiO2.

Silicon (Si)-doped metal oxides exhibit markedly enhanced gas sensing performance. Notably, ε-WO3, a metastable crystalline phase with exceptional acetone selectivity, can be stabilized by incorporating Si atoms into the framework. A representative example is the versatile directional orthogonal assembly strategy reported by our group[153]. In this method, PEO-b-PS is co-assembled with various Keggin-type heteropolyacids, followed by calcination-induced structural transformation. This approach enables the fabrication of heteroatom-doped MOS 3D multilayer cross-nanowire architectures featuring well-interconnected frameworks and uniform nanowire spacing. Si-doped WO3 nanowires synthesized through this method exhibit the ε-WO3 phase owing to the in situ introduction of Si from silicotungstic acid. Gas sensors based on these nanowires demonstrate excellent acetone sensing characteristics, including high sensitivity (LOD = 10.0 ppb), outstanding selectivity, fast response and recovery, and good stability. This superior performance is attributed to the combined effects of large surface area, abundant catalytic active sites, efficient electron transport along the nanowires, and the high electric dipole moment of ε-WO3

Sulfur (S) doping represents another effective strategy for enhancing the gas sensing performance of semiconductors, primarily by promoting charge transfer between oxides and sulfides. Shuvo et al. reported a S-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene gas sensor, which shows a greater toluene gas sensing performance compared to their undoped counterparts with unique selectivity and long-term stability [Figure 7D][156]. S doping leads to a 214% and 312% increase in sensing response for 1 ppm and 50 ppm toluene, respectively, compared to undoped materials. Simultaneously, it exhibits a pronounced response to extremely low concentrations of 50 ppb toluene, demonstrating its exceptionally low detection limit. Li et al. synthesized biomorphic mesoporous SnO2 using biomass carbon as a template and subsequently introduced sulfur through chemical vapor deposition to obtain S-doped SnO2[157]. The S-terminated sites of the resulting SnS2 phases act as active reaction centers for NO2 adsorption, thereby improving sensing performance. The S-doped SnO2 sensor exhibited an excellent response of 57.38 toward 100 ppm NO2, with a fast response time of 1.60 s and a detection limit of 10 ppb at room temperature. This performance enhancement was attributed to the formation of S-Sn-O bonds, which serve as electron-transfer bridges, reduce interfacial state density, increase carrier concentration, and generate more chemisorbed oxygen, thus accelerating NO2 reaction kinetics at room temperature. Xu et al. further achieved S-doped surface modification of SnO2 by sintering flower-like SnS2[158]. The obtained flower-like mesoporous S-doped SnO2 exhibited ultrahigh sensitivity to NO2 at low operating temperatures (50 °C), with an Rg/Ra value of 600 toward 5 ppm and a detection limit of 50 ppb (Rg/Ra = 11). The enhanced performance was attributed to the modified surface chemistry induced by S doping, which endowed the SnO2 surface with higher catalytic reactivity. In situ Raman spectroscopy and DFT calculations confirmed that S-doped SnO2 possesses superior catalytic activity and strong adsorption capability, and that its sensing performance is closely related to the S doping level.

Elemental doping represents a powerful strategy for tailoring the intrinsic physicochemical properties of MOS materials to achieve high-performance gas sensing. Different dopants operate through distinct mechanisms [Table 2]. Rare-earth elements, characterized by their partially filled 4f orbitals and variable oxidation states, are particularly effective in modulating band structures, enhancing surface alkalinity, and improving moisture tolerance, thereby enabling superior sensitivity under humid conditions. Transition-metal dopants, whose ionic radii are often comparable to those of host cations, can be readily incorporated into the lattice, significantly enhancing sensitivity by modulating carrier concentration, defect chemistry, and Ov. Non-metal dopants primarily influence surface electronic states and local electron distribution, offering notable potential for reducing operating temperatures by facilitating surface reactions and charge transfer. Future research should deepen the mechanistic understanding of the coupled dopant-host-target gas interactions, enabling targeted doping strategies that maximize sensitivity, selectivity, and stability.

Summary of elemental doping strategies

| Dopant | Advantages | Limitations | Performance enhancement effect | Typical elements |